Choose A Manufacturer

Overview of Early Greeneville Manufacturers

The map above shows the locations of several Greeneville manufacturing facilities in the year 1854. From 1835 until the early 1900s Greeneville was a major hub for the manufacturing of a variety of goods. The industrialist William P. Greene provided the entrepreneurial vision for Greeneville’s success. His Shetucket Company operated a major cotton mill that produced unfinished cotton cloth. The Norwich Bleaching, Dyeing & Printing Company finished the cloth. The Camp, Hall & Co., which later became the Chelsea Mfg. Paper Mill was a major producer of paper.

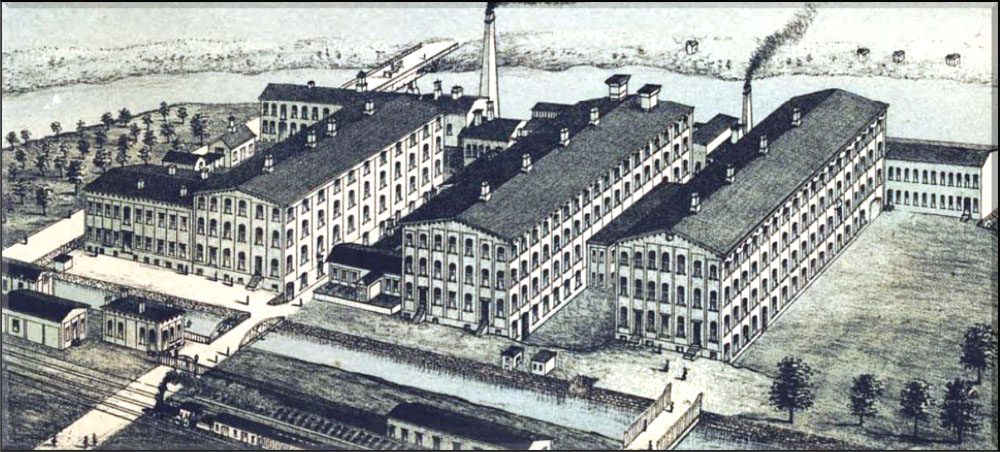

The lithograph below, published in 1861, provides a bird’s-eye view of how the businesses appeared from the east side of the Shetucket River.

Acknowledgements

“History of Norwich, Connecticut: From Its Possession From the Indians, to the Year 1866,” pp 612-613

“Map of New London County, Connecticut,” 1854, by Henry Francis Walling

“Norwich, Conn.,” 1861-1862, Lithograph by H. Knecht

1835-1923 Shetucket Company Cotton Mill

The Quinebaug Company, which manufactured cotton and woolen goods, was chartered in 1826. Their mill, erected on the Shetucket River, was purchased by the Thames Company before it went into operation. The mill was the first of the many large production facilities to be erected on the banks of the Shetucket River in Greeneville.

However, due to the Panic of 1837, the mill was forced to close because of the great depression and the stagnation of business throughout the United States. In 1840, the Thames Company mill in Greeneville was purchased by William P. Greene’s newly formed, Shetucket Company. In 1842, the mill burned down, but was quickly rebuilt. The new mill, built on the site of the burned mill, had a far greater capacity. It was named the Shetucket Company Cotton Mill.

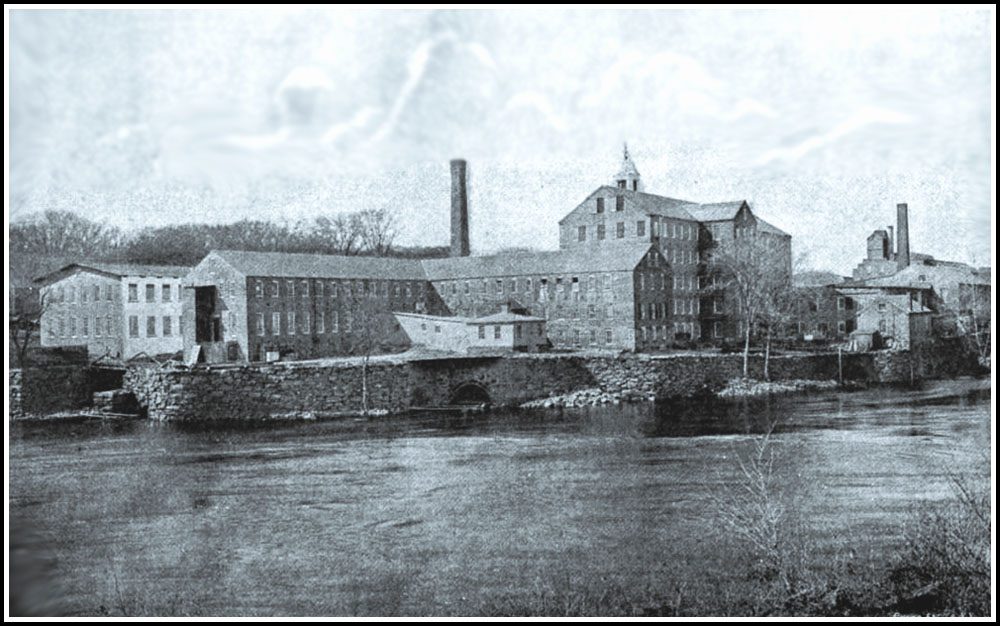

The Shetucket Company operated a cotton mill in Greeneville from 1840 thru 1923. It produced unfinished cotton cloth, which was sent to the Norwich Bleaching, Dyeing and Printing Company for finishing.

After the original mill (purchased from the Quinebaug Company) burned down in 1842, the Shetucket Company built a new, larger mill in its place. By 1865 the mill had 15,000 spindles in operation. By 1867 the mill had three buildings and a picker and dye house. They also added a two-story addition to their circa 1840 weaving mill and built a new brick office at 387 North Main Street by about 1880.

In 1888 the company employed 500 people, operated 20,000 spindles, and manufactured 6,000,000 yards of colored fabric. The average employee was paid $25 a month (approximately $700 a month in today’s dollars). The Ponemah Mills in Taftville produced three times more cloth and employed three times more people that the Shetucket Cotton Mill in 1888.

Although the Shetucket Company stayed in business until 1923, it began to scale back and lay off workers as early as 1915. Atlantic Carton (later the Atlantic Packing Group), a paper box manufacturer founded in 1916 on South Golden Street, took over the plant. In 2005, Atlantic Carton still used part of this complex and also owns the former office of the Shetucket Company on North Main Street. Unfortunately, the Atlantic Packing Group went out of business in November of 2016.

Acknowledgements

“History of Norwich, Connecticut: From Its Possession From the Indians, to the Year 1866,” pp 612-613, by Francis Manwaring Caulkins

“Norwich Connecticut: Its Importance as a Business and Manufacturing Centre and as a Place of Residence,” 1888, p 17, published by the Norwich Board of Trade

The complete list of sources may be found by clicking the “Bibliography” button, and, then typing “Shetucket Co” in the SEARCH box.

1840-1901 Norwich Bleaching, Dyeing & Printing Co.

Hugh Henry Osgood - President

Moses Pierce established the Norwich Bleaching, Dyeing, and Printing Company in 1840. Under his leadership the Bleachery grew from a dozen to more than 400 employees to become one of the largest textile finishing operations in the United States. At its peak in 1894 the Company had at least 20 buildings, five waterwheels and 2000 horsepower of steam. They produced 60 million yards of finished goods per year.

What is a Bleachery?

A Calendaring Machine from the year 1899

The “Bleachery” was a large operation where cotton cloth was “finished”. The finishing process converted the woven cotton cloth into a material that could be dyed or printed. The basic finishing steps were:

1) bleach the fabric,

2) pass it through a calendaring machine, and

3) dye and/or print a pattern on it.

Calendaring of textiles is a finishing process used to smooth, coat, or thin a material. It is done by pressing a continuous web of cloth between rollers to create a specific physical characteristic. With textiles, fabric is passed between calendar rollers at high temperatures and pressures. Calendaring is used on fabrics such as moiré to produce its watered effect and also on cambric and some types of sateen.

After the fabric was bleached and passed through a calendaring machine, it was dyed or had a printed pattern applied to it.

The Norwich Bleaching, Dyeing, and Printing Company was dissolved in 1901 and reorganized as the U.S. Finishing Company.

U.S. Finishing Company, Greeneville Plant

*Place cursor over photo to magnify

1901-1958 U.S. FINISHING COMPANY

The Norwich Branch of the U.S. Finishing Company was established at the site of the Norwich Bleaching, Dyeing and Printing Company in 1901. The company continued to finish fabrics similar to its predecessor.

The U.S. Finishing Company mercerized, dyed, printed and finished cottons, rayons, linens and wool mixtures. In 1914 there were 600 employees and they bleached, dyed and calendered 60 million yards of cotton goods. And, in 1944 it shipped more than 50 million yards of processed textile fabrics from the facility. The Greeneville plant closed in 1958.

Acknowledgements

“Norwich Connecticut: Its Importance as a Business and Manufacturing Centre and as a Place of Residence”, (1888), pp 17, 24, 25, 36, by the Norwich Board of Trade

1876 Map by O.H. Bailey, held at Library of Congress

The complete list of sources may be found by clicking the “Bibliography” button, and, then typing “Bleach” or “finishing” in the SEARCH box.

1840-1893 Chelsea Paper Manufacturing Company

*Place cursor over images to magnify

The manufacture of paper in Greeneville first began in 1835 with the Campbell & Hall Company. According to Info Source 1, the company was reorganized as the Chelsea Paper Company. however. Information sources (Photo Source 1) show the mill being called the Chelsea Manufacturing Paper Mill as early as 1840.

The company produced paper used for books and newspapers. For many years, their paper was supplied to the Harper Brothers, who used it for many of their publications, including Harper’s Monthly, Harper’s Weekly, and Harper’s Bazaar.

By 1860, the paper mill had grown significantly. It was claimed to be the largest paper-making establishment in the world. Its principal building was 375′ long (longer than the length of a football field). It had 180 employees and used 26 engines for grinding and cleaning the rags. An additional six machines converted the pulp into paper.

By 1870, the plant contained 19 paper-making machines. It remained in business under this name until 1890, producing an average of 30 tons of rag stock per day. In 1870, the company employed 200 men and 100 women.

The process for making paper in the 19th century required many steps. A detailed account of how paper was made at Chelsea Mills can be read by clicking the button on the left.

Mummy Paper

Mummy paper is paper made from linen used in mummy wrappings. The first recording of printed matter on authentic “mummy paper” was in a broadside that was published in 1858 in Norwich to advertise the upcoming 200th Norwich Jubilee. At the bottom of the sheet, there appeared this notice :

“This paper is made by the Chelsea Manufacturing Company, Greenville, Conn., the largest paper manufactory in the world. The material of which it is made was brought from Egypt. It was taken from ancient tombs where it had been used in embalming mummies.”

Copies of this broadside were printed and distributed at the September 7, 1859, parade at Norwich’s 200th Jubilee by members of the Chelsea Manufacturing Company. The paper company’s float was in the Sixth Division of the procession, and is described by John W. Stedman.

“Chelsea Manufacturing Co.— A paper cutting machine in operation, the produce of which was immediately transferred to a printing press of Messrs. Manning, Perry & Co., and Miss. Sigourney’s hymn of welcome was printed and distributed to the crowd. This carriage, drawn by four horses, was followed by about 100 of the employees of the paper mill, headed by a Scotch piper. They bore several banners with the inscriptions,

“Paper, the bridge uniting the past and present.”

“Humble we seem, yet science will clothe us with power,” (referring to a display of rags at the top of the banner );

“True heart;” “Labor conquers everything;”

“We welcome the returned ones home.”

Standard Cloth Binding

“The Norwich Jubilee,” a souvenir book published by John W. Stedman in the same period, boasted that the book was entirely a Norwich product and that the paper upon which it was printed had come from the Chelsea mills.

Since the book was printed by the same printer, in the same time period as the broadside, it is almost certainly also printed on Mummy Paper. This book is more likely than any other book in existence to have been printed on Mummy Paper.

The book was bound in two separate styles: a gold-tooled leather binding (by Lewis and Elisha Edwards) for those who wished something more elaborate and a publisher’s cloth binding for general sale and use.

A copy of the standard cloth-bound version is available in Otis Library. There are only two known copies of the deluxe leather-bound version.

*Click on images to magnify

Deluxe Leather Binding

“Hymn for the Bicentennial Anniversary of the Settlement of Norwich, Conn.,” at Brown University Repository

“Chelsea Mills, Norwich Connecticut,” by MummyMania.omeka.net

“Was This Hymn Printed on Mummy Paper?” by StrangeRemains.com

“Chelsea Manufacturing Company’s Paper Mills,” by Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, 02/24/1866

“The Norwich Jubilee, A Report of the Jubilee at Norwich, Connecticut on the 200th Anniversary of the Settlement of the Town,” 1859, by John W. Stedman

In 1893 the Chelsea Paper Company was reorganized as the Uncas Paper Company. Soon after the reorganization, the Uncas Paper Company built a new mill in Thamesville.

Acknowledgements

“National Register of Historic Places Registration Form for Greeneville,” 2005, United States Park Service

“History of Norwich, Connecticut: From Its Possession From the Indians, to the Year 1866,” p 618, by Frances Manwaring Caulkins

The complete list of sources may be found by clicking the “Bibliography” button, and, then typing “Chelsea Manufacturing” or “Uncas Paper” in the SEARCH box.

1872-1891 Norwich Lock Manufacturing Company

The Norwich Lock Company was formed in Norwich in 1865. A few years later, in 1872, it was reorganized as the Norwich Lock Manufacturing Company. By 1888, the company located on the banks of the Shetucket River, employed 275 hands and produced 2200 tons of merchandise per year. In 1888, it was one of the three largest lock manufacturers in the United States.

The Norwich Lock Manufacturing Company was located near the headquarters of present-day Norwich Public Utilities, at the end of South Golden Street. It produced an extensive line of builders’ hardware (mortise locks and associated items of door hardware) and a vast selection of padlocks, most of which were the wrought iron or smokehouse type. Many of these padlocks can be identified by an “N.L.M. Co.” marking.

*Place cursor over image to magnify

On February 25, 1879 Charles Beebe of Norwich was granted Design Patent No. 11,041 for an ornamental padlock. Some of these locks have shown up in various collections but have probably not been correctly identified to the manufacturer.

The 1888 Norwich Lock Mfg. Company catalog offers an extensive line of builders’ hardware, wrought iron padlocks, and a series of “Ornamental Bronzed Iron Padlocks.” An example of one of their mortise door knob locks, made of bronze, is pictured on the left.

According to one source, the company may have produced parts for Norwich gunmakers and possibly even sold guns.

*Place cursor over the image to magnify

*Place cursor over photo to magnify

The photo shown on the left illustrates two story padlocks made by the Norwich Lock Mfg. Co. Note the fine detail on both the Masonic Story lock and a Moon & Star Story lock. The Masonic Story lock could be opened by the push key shown. The company made several story padlocks similar to these in the late 1800s. They were generally made of cast iron and were highly decorated.

Today these locks are rare and command a high price at auction. A Masonic Story Lock very similar to the one shown here sold at auction for $1,925 in 2012.

The company moved to Roanoke Virginia in 1891 and remained in business there until 1905.

Acknowledgements

“Early Locks and Lockmakers of America,” 1976, by Thomas F. Hennesy

“Norwich Connecticut: Its Importance as a Business and Manufacturing Centre and as a Place of Residence,” 1888, p 27, by the Norwich Board of Trade

The complete list of sources may be found by clicking the “Bibliography” button, and, then typing “Norwich Lock” in the SEARCH box.