Choose An Historic Event

Click the icon to learn of Floods, Fires, and other Calamities in Norwich

1643 Battle of the Great Plain

*Place cursor over images to magnify

On September 17, 1643 the Battle of the Great Plain was fought on a large open field on present-day CSCC Three Rivers campus. On this field Uncas let the great Narragansett sachem proudly display his overwhelming army of warriors. As it happens, it was also a place where the Mohegan bow and arrow would be effective on a very large scale. Miantonomo typically attacked with upward of 700 warriors. While Uncas sometimes maintained as many as 500 warriors, they were primarily defensive and spread thinly. Uncas usually led between 100 and 200 elite warriors into battle.

The Mohegan warriors were the best and brightest warriors from all the other nations because Uncas welcomed all nations, offered the greatest freedom, and upheld the Native American traditions and virtues.

The Mohegans were greatly outnumbered by the Narragansett, but Uncas had a plan. Uncas would ask Miantonomo to fight him single handed in mortal combat in the open field. He told his warriors that when Miantonomo refused to fight him, Uncas would drop to the ground and that would be the signal for the Mohegan warriors to fire all their arrows at the Narragansett warriors.

When Uncas fell to the ground as though he were dead, the Narragansett were startled and confused. Volleys of arrows struck the Narragansett but carefully missed the area where Uncas and Miantonomo were. The plan worked and most of the Narragansett warriors were finished off within a minute.

The plaque shown on the left which commemorates the battle is on the CSCC Three Rivers campus

Acknowledgements

“History of Norwich, Connecticut: From its Settlement in 1660, to January 1845,” (pp 15-19), by Frances Manwaring Caulkins

Bolton Historical Society

“Norwich Board of Trade Quarterly,” (1909)

Bob Dees

The complete list of sources may be found by clicking the “Bibliography” button, and, then typing “Great Plain” in the SEARCH box.

1760-1930 Annual Barrel Bonfires

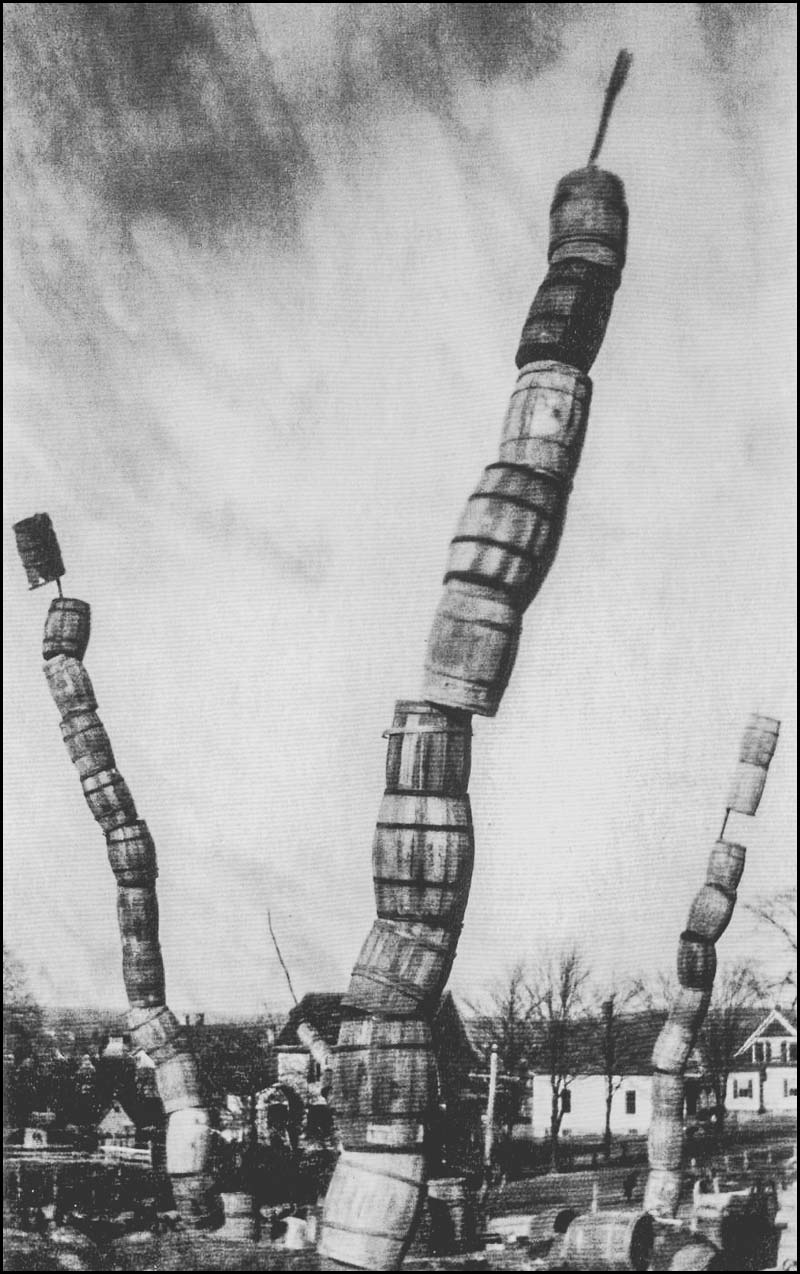

Barrel Bonfire circa 1895

On Lanman’s Hill (Present-day Mount Pleasant)

From approximately 1760 to 1930 Norwich had a custom of creating spectacular bonfires made of wooden barrels stacked on a pole. For many years the custom was practiced annually on Thanksgiving evening.

The following is an excerpt from Info Source 1.

“The annual Thanksgiving was a day of great hilarity, although its time-honored essential characteristic was a sermon. A peculiar adjunct of this festival in Norwich was a barrel bonfire. A lofty pole was erected, around which a pyramid of old barrels was arranged, large at the platform, but a single barrel well tarred forming the apex. The burning of this pile constituted the revelry or triumphant part of the entertainment, and was considered by the young as indispensable to a finished Thanksgiving.”

“When built upon the plain, the whole valley was lighted up by the blaze, like a regal saloon : and when upon a height, the column of flame sent forth a flood of light over woods and vales, houses and streams below, producing a truly picturesque effect.”

The custom of barrel bonfires in Norwich predates the Revolutionary days. For upward of a hundred years the hill tops in and around Norwich blazed each Thanksgiving night with hundreds of barrels. The tasks of collecting and tending the fires was faithfully carried out by youngsters of the town.

In Norwich barrel bonfires were set ablaze on Jail Hill, Cliff Terrace, Fox Hill, Ox Hill, Bean Hill, Mount Pleasant and Lake Street. The last of the barrel burnings was on Lake Street.

In addition to using barrel bonfires for Thanksgiving celebrations, for many years, they were also used as beacons to welcome home absent sons and daughters. On the Saturday evening before the 1901 Old Home Week celebration in Norwich, a huge barrel bonfire was lit on Lanman’s Hill (present-day Mount Pleasant). The beacon blaze was intended to make returning Norwichians feel at home. On that night the chairman of the barrel burning committee secured an enormous quantity of barrels, boxes, crates, railroad ties and set it off at 8:30. The mammoth pile smoldered long into the wee hours of the morning.

The custom of celebrating a day of thanksgiving and burning barrel bonfires antedates the first European settlers arriving in North America. In the early 1600s in England there were many Church of England designated days of thanksgiving. Religious reforms reduced the number of church holidays down to 27 and added “Days of Thanksgiving” which celebrated English national good fortune, military success or other occasions worthy of thanksgiving.

One such day was “Guy Fawkes Day”. After the year 1605, this day was celebrated annually on November 5th. England celebrated day in remembrance of Guy Fawkes’ failed attempt to blow up the Parliament. The holiday was marked by the burning of barrel bonfires. (Refer to inset below)

As Pilgrims, Puritans and others left England for North America many brought their thanksgiving traditions with them. In the mid-1700s, Guy Fawkes Day evolved to Pope Day in New England. Later, in 1789, George Washington formally proclaimed the first national Thanksgiving Day.

Guy Fawkes Day

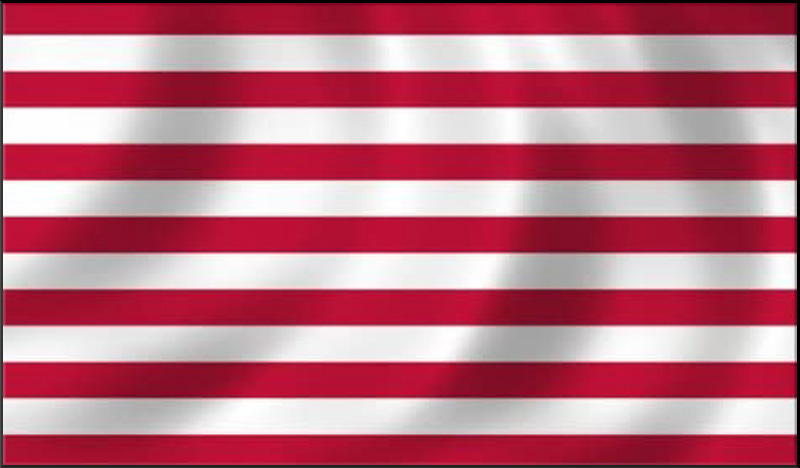

Great Britain’s Bonfire Night, also known as Guy Fawkes Day, is associated with the tradition of celebrating the failure of the Gunpowder Plot of November 5, 1605. Guy Fawkes, and eight other conspirators, plotted to blow up the Houses of Parliament with gunpowder. They planned to assassinate King James, his son, and members of both the House of Lords and the House of Commons due to the established government’s lack of tolerance of Catholicism.

The plan failed when a search party found 36 barrels of gun powder and Guy Fawkes, with matches in his pocket, in a room located beneath the Houses of Parliament. Fawkes, and his surviving co-conspirators, were all found guilty of high treason and sentenced to death in January 1606.

Londoners began lighting celebratory bonfires, and, in January 1606, an act of Parliament designated November 5 as an annual day of thanksgiving. Guy Fawkes Day festivities soon spread as far as the American colonies, where they evolved into what became known as Pope Day. In keeping with the anti-Catholic sentiment of the time, British subjects on both sides of the Atlantic would burn an effigy of the pope.

Guy Fawkes was an anti-establishment protestor. He and his group strongly believed that King James’ government should be more tolerant of the Catholic religion. In the 2005 movie, V is for Vendetta , illustrator David Lloyd created a mask which features a smiling face with red cheeks, a wide moustache upturned at both ends, and a thin vertical pointed beard. The mask is a stylized depiction of Guy Fawkes and is called a “Guy Fawkes Mask”. The mask is used by anti-establishment protestors around the world.

“On Thursday evening last, a young man by the name of Cook, aged 19, was instantly killed in this town by the discharge of a swivel. The circumstances as near as we can recollect, were as follows:

In celebration of the day, (being Thanksgiving,) a large number of boys had assembled, and by pillaging dry casks from the stores, wharves, etc. had erected a bonfire on the hill back of the Landing, and to make their rejoicings more sonorous, fired a swivel several times; at last a foolish fondness for a loud report induced them to be pretty lavish of their powder — the explosion burst the swivel into a multitude of pieces, the largest of which, weighing about seven pounds, passed through the body of the deceased, carrying with it his heart, and was afterwards found in the street 30 or 40 rods from the place where it was fired. While the serious lament the unhappy accident, they entertain a hope that good may come of evil, that the savage practice of making bonfires on the evening of Thanksgiving may be exchanged for some other mode of rejoicing, more consistent with the genuine spirit of Christianity.”

What is a Swivel Gun?

A swivel gun (or simply a swivel) is a small cannon mounted on a swiveling stand or fork which allows a very wide arc of movement. They were used for signaling purposes and for firing salutes. They were also used by whalers, where bow-mounted swivel guns fired harpoons. Swivel guns, mounted on punt guns, were also used to shoot flocks of waterfowl.

They could be quickly mounted on any ship. Pirates used these guns to protect themselves from intruders attempting to board their ships.

Swivels could fire all types of ammunition, but especially grapeshot.

Acknowledgements

“History of Norwich, Connecticut: From Its Possession From the Indians, to the Year 1866,” (pp 331,412), by Frances Manwaring Caulkins

“Old Home Week, Norwich, Conn., September 1-7 1901,” pp 8-12, published by Bulletin Print

“Old Houses of the Ancient Town of Norwich, 1600-1800,” (1895), pp 19-20, by Mary Elizabeth Perkins

“Barrel Burning Lit Up the Thanksgiving Sky in Norwich,” 11/30/2008, by Bill Stanley

The complete list of sources may be found by clicking the “Bibliography” button, and, then typing “bonfire” in the SEARCH box.

1765 Norwich Erects Liberty Tree

On March 22, 1765 Britain passed the Stamp Act and it went into effect on November 1, 1765. This legislation was designed to force American colonists to help pay Britain’s war debt incurred during the French and Indian War. The colonists immediately protested and secret organizations called “Sons of Liberty” sprang up throughout the colonies.

Info Source 1 states that the headquarters for the Sons of Liberty in Connecticut was in Norwich, and that Major John Durkee, was a very active and influential member of the organization.

Although the Stamp Act had not yet even gone into effect, in the autumn of 1765, a liberty tree was erected on the Norwichtown Green. The Liberty Tree was a lofty pole erected in the center of the Green, decked with standards and appropriate devices, and crowned with a cap. A tent was erected under it, called the Pavilion. People assembled here almost daily to hear news, make speeches and encourage each other in the determination to resist all opposition. It was a strong symbol of Norwich’s protest of the Stamp Act.

Jared Ingersoll, of New Haven, had been appointed by the Connecticut General Assembly to be the tax collector in Connecticut. In August 1765 Ingersoll was hung and burned in effigy in Windham. A month later the citizens of New Haven requested that he resign. However, he refused to do so.

It was amid such demonstrations as these against the Stamp Act that a body of several hundred men, gathered from Norwich and neighboring towns set out on horseback to confront It was amid such demonstrations as these against the Stamp Act that a body of several hundred men, gathered from Norwich and neighboring towns set out on horseback to confront Jared Ingersoll

At this point more than 1000 people had joined the group and Major John Durkee demanded Ingersolls’s resignation. After several hours of Ingersoll’s delay tactics Major Durkee demanded his resignation again. Ingosoll then requested to wait to ‘learn the sense of the government’ (i.e. ask the opinion of the General Assembly). Major Durkee replied, “HERE is the sense of the government and no man shall execute your office”. Ingersoll replied “I ask for leave to proceed to Hartford”. Durkee replied “You shall not go two rods till you have resigned”. Then, finally Ingersoll said “This cause is not worth dying for”, and he resigned. At that point-in-time, Major Durkee compelled Ingersoll to shout “Liberty and Property” three times before the crowd. Three Huzza!’s were given and the whole company immediately dispersed without the least disturbance.

When the Stamp Act went into effect on November 1, 1765 there were neither stamps or stamp masters in Connecticut. Major John Durkee played an important role in protecting the rights of colonists throughout Connecticut. The Stamp Act was repealed on November 18, 1766.

Jared Ingersoll fled to Europe from 1773 to 1776 to avoid the growing political conflict between Britain and the Thirteen Colonies. In 1778, having committed himself to the cause of American independence, he returned to Philadelphia and won election to the Continental Congress.

The first anniversary of the repeal of the Stamp Act was celebrated in Norwich with peculiar festivity. In a communication to the Hartford Courant, the proceedings are recorded as :

“Norwich, March 19, 1767 : Yesterday, P.M. a number of gentlemen of this town assembled under Liberty Tree to celebrate the day that his Majesty went in his royal robes to the House of Peers and seated on the throne gave his assent to the Repeal of the Stamp Act, for which may he be forever blessed in family and person with all the blessings of heaven”.

Acknowledgements

“A History of Wilkes-Barré, Luzerne County Pennsylvania,” Vol. 1, p 482, by Oscar Jewell Harvey, (1909)

“Records and Papers of the New London County Historical Society Vol. 3,” pp 260-263, (1906), by Amos A. Browning

The Connecticut Society of the Sons of the American Revolution

The complete list of sources may be found by clicking the “Bibliography” button, and, then typing “Liberty Pole” in the SEARCH box.

1855 New London County Fair in Norwich

The first New London County Agricultural Society was formed 1818 and continued in operation for five to six years. The group held an annual fair alternatively at Norwich and New London. The association declined and folded after a few years.

A new county agricultural group was formed on April 12, 1854 in the Norwich Town Hall. Subsequently, the New London County Fair was held annually at the fairgrounds in Norwich from 1855 until the late-1930s. The fair, held in early September, featured many agricultural based exhibits and fireworks.

The fair’s events and activities held the wonder of spectators. For several years the fair featured horse racing. The 1905 postcard, shown below on the left, portrays a jockey on a sulky during a harness race. The postcard on the right, produced in 1911, features a young woman feeding the horse “A Fair Treat”.

For many years the county fair was held at the fairgrounds in the area of present-day Three Rivers Community College. In the 1910s, fair goers could ride a trolley from anywhere in the city to the trolley stop, located on West Main Street near present-day East Great Plain Fire Department. After a day of fun and an evening filled with fireworks, they could easily walk back to the trolley car and return home.

In some years a circus was held inside a big top tent on Fairground Circle, located across the street from the fairgrounds. To make this trip, visitors would first ride the trolley from anywhere in the city to the end-of-the-line stop near the present-day Staples Store. Then, they would hop aboard a surrey and ride up Surrey Lane to the big top tent.

After the Benevolent Protective Order of Elks purchased the East Grand Plain land, the Elks’ Fair was still held in this area. Even today the streets in that area of Norwich still carry the names : Surrey Lane, Fairground Circle, County Fair Road, Elk Drive, and Manwaring Road.

Like many agricultural fairs today, many types of animals were on display at the county fair. The photo shown below depicts oxen at the New London County Fairgrounds in Norwich in 1914.

Some of the fairs featured aerial displays. The first fair held in Norwich, in 1855, featured the aeronaut, M. Paulin and his balloon. He entertained the show with a balloon ascension, remaining an hour in the air and descending at South Kingston Rhode Island.

Later, in 1913 one airship display ended in a crash into Maplewood Cemetery. See the inset below.

New London County Fair Norwich

1913: Airship from Fair Crashes in Maplwood Cemetery

The 1913 New London County Fair was held in Norwich, Connecticut, on September 1st, 2nd, & 3rd. On the last day of the fair, a young aviator identified as Knox Martin was giving demonstration flights of his Curtis bi-plane. During the course of the day he made four successful flights, taking off from the fair grounds, circling the city, and landing back at the fair. At 3:00 p.m. he took off on his fifth flight and headed in a southerly direction, but before long his motor started skipping so he turned back towards the fair grounds. As he was making his approach at an altitude of 700 feet the motor quit and Martin began looking for a clear area to land. Seeing the Maplewood Cemetery below, he made for it, but as he neared the ground he saw that he was going to collide with a large tree, so he made a sharp turn to avoid it. While doing so he was pitched from the plane and fell to the ground. Meanwhile the airplane continued on and wrecked in the cemetery.

Surprisingly, Martin only received bumps and burses. By 3:45 p.m. he was back at the fair grounds waving to cheering crowds.

Info Source 2

As a part of Norwich’s 250th Anniversary one of the first flying ships flew over the fairgrounds in East Great Plain for several minutes. Captain Thomas S. Baldwin piloted the dirigible.

Another interesting tidbit should be noted. For most of her life, during this time period, Dr. Ier J. Manwaring and her family lived on a 100-acre farm across from the fairgrounds, on the west side of New London Turnpike. After retiring from her medical practice, she devoted herself to agricultural interests, raising Cheviot sheep and holding sheep-shearing contests.

Acknowledgements

“History of New London County, Connecticut: With Biographical Sketches of Many of Its Pioneers and Prominent Men,” 1882, p 320, by Duane Hamilton Hurd

Airship Smashed At Norwich Fair, 09/04/1913

“The Faith Jennings Collection” p 176, by Faith Jennings & Bill Stanley,

The complete list of sources may be found by clicking the “Bibliography” button, and, then typing “County Fair” in the SEARCH box.

1859 Norwich Bicentennial Jubilee

The celebration of Norwich’s 200th Jubilee, on September7-8, 1859, was a huge affair that lasted for two days. The image shown here is of the procession that began at 10:00 o’clock on the 1st day of the Jubilee at Franklin Square. The procession included 11 divisions of bands, military units, local officials, firefighters, members of local businesses, citizens from surrounding towns, and many others.

The procession began at Franklin Square and proceeded north on Franklin Street. The parade passed underneath a huge banner with the inscription “NORWICH, THE ROSE OF NEW ENGLAND” on Broadway. When the procession arrived at the Central Grammar School (near Little Plain) the school’s students sang a hymn before the President of the Day Governor William A. Buckingham, the Procession Marshal Henry W. Birge, the former President Millard Fillmore, and other high-ranking officials.

The procession continued to downtown, passing by the Wauregan House, and then turned northward, up Washington Street.

The two and a half mile route took the marchers approximately two and a half hours to complete.

Click on the “Route Details : Interactive Map” button to see expanded map with more details.

The procession ended at Williams Park (known today as Chelsea Parade), where a large tent had been erected for the occasion. The Norwich Free Academy, opened only 3 years earlier, can be seen in the background. Inside this tent, which housed 2,500 people, Governor William A. Buckingham, the “President of the Day”, addressed the audience.

It should be noted that the population of Norwich was approximately 5,000 in 1859. This means that the procession tent was large enough to host about half the entire population of Norwich.

After Governor’s Buckingham address Reverend Hiram P. Arms, the minister of the First Congregational Church offered a prayer. Then a choir sang a hymn written by Lydia Huntley Sigourney, especially for the occasion.

Subsequently, Daniel Coit Gilman, a native of Norwich, son of former mayor William Charles Gilman, and the librarian of the Yale College library, delivered a detailed history of the first two hundred years of Norwich history. You may read the complete copy of his discourse when you click the link below.

The second day of the Jubilee was filled with speeches, prayers, poems, songs, an elegant dinner, and a formal ball. The day was ushered in by the firing of cannons and the ringing of church bells at sunrise.

At 9:00 o’clock, a procession marched to the site of the proposed monument honoring Major John Mason in the Yantic Cemetery. This procession included local and nearby town Masonic orders, officers of the celebration, invited guests, and the people of Norwich. After several prayers and blessings, John A. Rockwell delivered an address that discussed the life and times of Major John Mason and many other of Norwich’s founding fathers.

Upon the conclusion of Rockwell’s speech, the song “To The Future Inhabitants of Our Norwich Home”, music by H.W. Amadeus Beale of Norwich, and lyrics by Miss Josephine Tyler, was sung.

Donald G. Mitchell then delivered an address that bespoke of the history and development of Norwich and her citizens.

After Mitchell’s speech the poem, shown on the left, was read. The poem was written for the Jubilee by Anson G. Chester.

Anson G. Chester was born in Norwich. He became a poet and a minister. He served as a missionary to the Choctaw Indians and as pastor to the Mohegan Indian Church.

He wrote many poems, including “The Tapestry Weaver”, which became a classic. In 1868, he wrote and delivered a poem to memorialize the 150th Anniversary of Franklin, CT.

After Chester’s poem was read the song “200 Years Ago, A Bi-Centennial Ode”, music by H.W. Amadeus Beale of Norwich and lyrics by George Canning Hill, was sung

Only verse IV of the poem is shown in the illustration. The complete poem may be found in John Stedman’s book, listed in the source below.

The Jubilee Dinner, hosted inside the tent on Chelsea Parade, was held on the afternoon of the second day. It was an elegant affair, attended by more than 2,500 people. In addition to the standard Bill of Fare, the menu also included leg of mutton, boiled tongue, jellied tongue, succotash, Connecticut pudding, Indian pudding, and tongue sandwiches.

A formal Ball was hosted in the tent on the last evening of the Jubilee. The women wore Colonial garb, featuring long skirts, aprons and bonnets. The men wore beards and Abe Lincoln stove-pipe hats. The ball brought the Jubilee to a joyful, successful conclusion.

John Stedman’s book, contains a wealth of information about the Jubilee and the history of Norwich prior to 1859.

Acknowledgements

“The Norwich Jubilee A Report of the Jubilee at Norwich, Connecticut on the 200th Anniversary of the Settlement of the Town (1859) ,” by John W. Stedman

The complete list of sources may be found by clicking the “Bibliography” button, and, then typing “Jubilee” in the SEARCH box.

1859 Norwich Gets Its Nickname

Many have speculated about how Norwich got its nickname, “The Rose of New England”

On May 24, 1909 The Norwich Bulletin wrote

“At last, we have authentic information that Henry Ward Beecher was the author of “The Rose of New England”, and Edward T. Clapp was the perpetrator of it. In the year 1850 or 1851, when the late Henry B. Norton was returning from abroad on an ocean liner, he made the acquaintance of Henry Ward Beecher.”

“Mr. Beecher was then a contributor to the New York Independent, and while spending the day with Mr. Norton in Norwich, entered the greenhouse at the foot of the garden and wrote the letter to that paper that first called Norwich ‘The Rose of New England’ .”

Unfortunately, the May 1909 Norwich Bulletin article shown above was erroneous. Several months later, July 1909, Norwich celebrated its 250th anniversary of the town of Norwich. A detailed account of this historic event was chronicled by William C. Gilman (Info Source 1).

In his introduction, pages 10-11, Gilman discusses the origin of Norwich’s nickname, “The Rose of New England” in unambiguous terms. He states that the Rose of New England term does not appear in any of Henry Ward Beecher published writings.

Dorothy Perkins Rose

General Jacqueminot Rose

by William C. Gilman (1912)

” … Norwich gradually became, as it continues to be, a cluster of semi-detached villages radiating from the Landing as a common center, and including the pleasant plains of Chelsea a half-mile from the Norwich, port, the Falls, Up-Town, Bean Hill, Yantic, West-side, Thamesville, Laurel Hill, East Norwich, Greeneville, Taftville and Occum. These are surrounded by hills, Plain Hill, Ox Hill, Wawecus Hill, and others, occupied for the most part as farms and woodlands. These villages have sometimes been fancifully regarded as the petals of the Rose of New England.” “The authorship of this felicitous appellation has been ascribed to Henry Ward Beecher, but does not appear in his published writings, not even in his famous Norwich ‘Star Paper,’ which after sixty years is still as perfect a pen picture of the old town as if he had written it in 1909.” “This tradition as to the name, received by Jonathan Trumbull from Edward T. Clapp, remains undisputed, and may be accepted as veritable history. When the Committee on Decorations for the Bi-centennial celebration in 1859 was considering an appropriate designation for the town, the chairman, James Lloyd Greene, said, ‘Well, she is a rose, anyway!’ “ “Yes, responded Mr. Clapp, Norwich is the Rose of New England. That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet, and whether Norwich be called Dorothy Perkins, or Killarney, or General Jacqueminot, it will still be the American Beauty, the Rose of New England.”So … with these words in mind, the idea of referring to Norwich as a rose should be attributed to J. Lloyd Greene and the nickname was coined by Edward T. Clapp in the year 1859.

The poem “Old Norwich Town,” shown on the left, was written by Livia Ione Young (1867-1943). She wrote a collection of Norwich themed poems entitled “At Evening Time – Old Norwich Town” that was published in 1907. She is buried in Maplewood Cemetery.

*Place cursor on image to magnify

Acknowledgements

“The Celebration of the Two Hundred and Fiftieth Anniversary of the Settlement of the Town of Norwich Connecticut and of the Incorporation of the City the One Hundred and Twenty-Fifth, July 4, 5, 6, 1909”, pp 10-11, (1912), by William C. Gilman

“At Evening Time – Old Norwich Town,” 1907, by Livia Ione Young.

“Old Norwich Town,” by Livia Ione Young, Otis Library Flickr Collection

The complete list of sources may be found by clicking the “Bibliography” button, and, then typing “Nickname” in the SEARCH box.

1876 Almshouse Fire

Norwich has made provision for poor and/or mentally disabled people for hundreds of years. Throughout New England, prior to 1800, poorhouses frequently settled near adjacent farms where paupers could labor to raise their own food, care for animals, and contribute to their welfare and upkeep as much as possible. These farms were commonly called “poor farms” the extent and locations of which varied widely from town to town.

From 1790-1800 Norwich citizens in need of these services were sent to the Hazen Farm in Baltic. The town of Norwich provided funds for residents at the farm, however, due to its location far away from the hub of Norwich, the costs were high.

In 1800 a more cost-effective poor house, located on Washington Street near the heart of Norwich proper, was established. The facility, the first Almshouse in Norwich, put into service in 1800. However, as the city prospered, successful merchants, bankers, manufactures and sea captains who owned mansions on Washington Street forced the poor farm to move to a more suitable location.

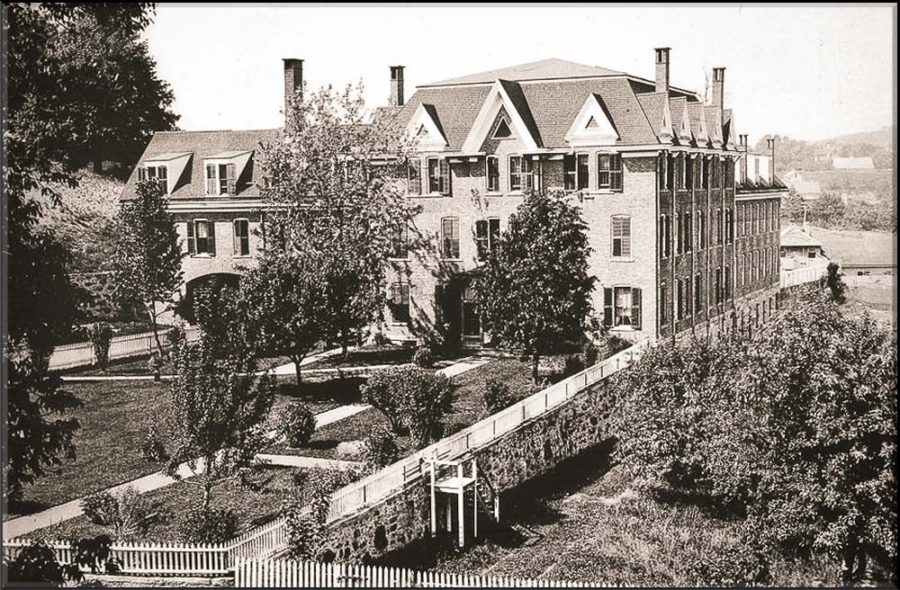

In 1819 a new Almshouse was built on the west side of the Yantic River, near the present-day Estelle Cohen Dog Park on Asylum Street. Over the years, both poor and mentally disabled were cared for in the facility.

Unfortunately, on March 12, 1876 a fire broke out that devastated the Almshouse. The photo on the left shows a view of the facility after the fire. Sixteen mental patients, locked in their rooms, were unable to escape and burned to death. The facility, having been deliberately removed to this remote section of town, burned before help arrived.

Info Source 1 provides a detailed account of the tragedy.

The Almshouse was rebuilt and the new facility, as appeared in 1898, is shown on the left. Upon the opening of the Norwich State Hospital for the Insane in October 1904 the mentally disturbed residents from the Almshouse were moved to the Hospital.

The Almshouse was ultimately abandoned, sold and was destroyed by fire in 1956.

Acknowledgements

“Alms House Conflagration 1876,” by Beryl Fishbone, 11/14/2016

Public Domain: Posted on Facebook (Dave Oat)

The complete list of sources may be found by clicking the “Bibliography” button, and, then typing “Almshouse” in the SEARCH box.

1876 Flood of 1876

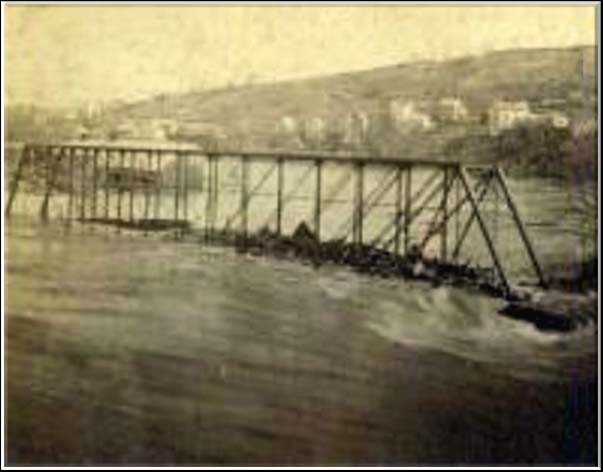

Two weeks after the Almshouse fire, in late March 1876, Norwich suffered a flood that caused widespread damage and loss of life.

Heavy rains, over an extended period, filled the reservoirs along the Yantic, Quinebaug, and Shetucket Rivers. The first notice that Norwich citizens heard was the alarm of the city hall bell. The bell was a summons for assistance to clear the warehouses on the riverfront, as the immense volumes of water discharged from the three rivers. The water level of the Thames rose above the wharves and serious destruction of property resulted throughout much of downtown Norwich.

Thankfully, the Greeneville Dam held despite twelve feet of water flowing over it. The Taftville Dam also held with ten feet of water flowing over its rollway. The most serious damage was done to the Baltic Dam. Its bulkhead washed away and the dam was undermined.

Seven people died and the loss was estimated at $500,000 ($12,000,000 in today’s dollars). The Norwich & Worcester sections of the New York and New England Railroad, and the New London Northern Railroad was badly washed out in several places.

Acknowledgements

Hartford Daily Courant 03/27/1876

Connecticut Historical Society

The complete list of sources may be found by clicking the “Bibliography” button, and, then typing “flood” in the SEARCH box.