May 1775-Sep 1783 : Norwich in the Revolutionary War

The Second Continental Congress first convened on May 10, 1775. This was the first of many meetings of the provisional government of the united colonies. Some of the major achievements of the congress included :

a) Successfully managing the war effort, and,

b) Drafting the Articles of Confederation, and,

c) Drafting the first Constitution of the United States, and,

d) Creating the Continental Army and Continental Navy.

In July 1775 the Declaration of the Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms, essentially a declaration of war, was initiated by the Congress primarily due to their objection to the British Parliament’s taxation policies and lack of colonial representation.

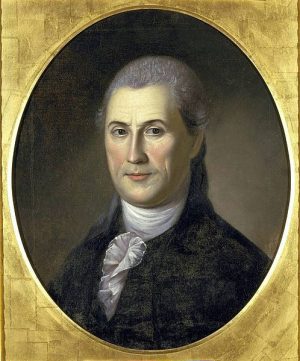

Samuel Huntington, of Norwich, was a delegate to the Second Continental Congress in 1776, 1777-1781, and 1783. He was elected President of the Second Continental Congress at the September 28, 1779 meeting. He served in that capacity until July 10, 1781. He was an outspoken critic of the Intolerable Acts. He played an important part in furthering the rights of the colonists.

On November 15, 1777 the congress had passed Articles of Confederation. These articles formed the first framework for an independent government in America. The articles were sent to each of the states for ratification and the last state, Maryland, ratified the articles on February 2, 1781.

On March 1, 1781 the Articles of Confederation went into effect. This was the first day the all the thirteen states were united under a single government. Samuel Huntington was the President of the Continental Congress on that day, and, many say that gives him the right to be honored as the First President of the United States.

Samuel Huntington’s home in Norwich, 34 East Town Street, is on the National Register of Historic Places.

Before the war broke out, Joshua Huntington operated several successful businesses in Norwich. However in early 1775 he answered the first call to arms. He fought at the Battles at Lexington and Concord in Massachusetts. Two weeks later, on May 1, 1775, he was commissioned as a First Lieutenant into the Continental Army. Soon thereafter, he participated in the Siege of Boston. In June 1775, after being encamped on Prospect Hill the site of American fortifications, he returned home.

Huntington remained active in the army while in Norwich in several capacities. He was engaged in securing ships for the war effort and in outfitting ships for privateers. Joshua Huntington was also an agent for supplying the French army at Newport with provisions and was in charge of refitting the British vessels that had been captured by the French navy.

In 1776 he also fought in the New York and New Jersey campaign.

The availability of reliable, up-to-date news and information concerning the revolution was critical the patriots. From the onset of the revolt Christopher Leffingwell was the best source of information in Norwich. He was the one to whom the first news of Lexington and Concord was addressed, and to whom the Huntingtons and Trumbulls requested supplies when troops were called into action. He was a Revolutionary War correspondent and a provider of invaluable provisions for the patriots.

Even before any shots were fired Christopher Leffingwell was a member of Connecticut’s Committee of Correspondence, a conduit through which ideas of American independence from Britain were nurtured. These ideas helped fuel the American colonist’s Declaration of Independence.

It is believed that throughout the war Leffingwell had access to special avenues of information. He had both imagination and foresight enough to bring General Washington to him when the British troops appeared likely to have split our army in two. No one, perhaps, in Connecticut took a more strategic part in the War, albeit always as a private citizen, than Christopher Leffingwell. The contents of one of his letters to George Washington is preserved in the United States National Archives.

The Norwich rebels frequently met in his tavern, the Leffingwell Inn. Patriots frequented his tavern to purchase tobacco and rum, read the newspaper and discuss political issues. His grandfather, Ensign Thomas Leffingwell, first established the tavern in 1701.

Connecticut Committee of Correspondence

Christopher Leffingwell of Norwich was an active member of a Committee of Correspondence in Connecticut.

The Committees of Correspondence were the American colonies’ first institutions for maintaining communication with one another. They were first organized in the decade before the Revolution, when the deteriorating relationship with Great Britain made it increasingly important for the colonies to share ideas and information.

Connecticut formed its Committee of Correspondence prior to July 1773. It successfully organized common resistance to the British Tea Act of 1773 and even recruited physicians who wrote drinking tea would make Americans “weak, effeminate, and valetudinarian for life.”

The function of the committee was to inform the voters of the common threat faced by all the colonies and to disseminate information from the main cities to the rural hinterlands where most of the colonists lived. As the news was typically spread in hand-written letters or printed pamphlets to be carried by couriers on horseback or aboard ships, the committees were responsible for ensuring that this news accurately reflected the views of their parent governmental body on a particular issue and was dispatched to the proper groups.

Many correspondents were also members of the colonial legislative assemblies and were active in the secret Sons of Liberty or even the Stamp Act Congress of the 1760s.

Christopher Leffingwell operated several manufacturing enterprises in Norwich; a chocolate mill, a wool finishing mill, a grist mill, a stocking factory and a paper mill. All these production facilities increased colonist’s self-reliance and decreased the need for British made goods. The paper mill was of special interest.

In 1766, shortly after the Stamp Act became law, Christopher Leffingwell erected the first paper mill in Connecticut. The mill, located in Norwich adjacent to “No-man’s Acre” (near present-day’s Falls Mill Condominiums) produced various types of paper for writing, printing, wrapping and other uses. Due to his role of regional correspondent, Leffingwell most assuredly foresaw the future need for a reliable source of locally produced paper.

The readily available local supply of writing paper increased Leffingwell’s ability to more accurately interact with his colleagues, allowing both encrypted and open formats. It is highly likely that Joshua Leffingwell was acquainted with, and worked together with, Gov. Jonathan Trumbull’s official Post, Jesse Brown of Norwich.

In addition to the well-known military and ideological leaders, there were a number of local Norwich civilians that supported the war effort. Unlike the British and French Armies, most of the colonists used weapons from their state’s militia store or their own home. Many muskets were produced locally by various gunsmiths. The muskets used were known as Committee of Safety muskets because they were funded by the fledgling local governments.

In the 1770s William Lax made cannon carriages in his shop on the Norwichtown Green. In the 1775s Nathan Cobb and John Leffingwell operated a gun shop in Norwich that that made and repaired soldier’s firearms. Their shop was located on Washington Street in Norwichtown.

During the Revolutionary War time period a foundry called the “Backus Ironworks”. It was located in the area between Bean Hill and present-day New England Central Railroad, (near Yantic River Inn). The foundry cast anchors and cannons for the Connecticut Navy. Backus Ironworks was owned and operated by Captain Elijah Backus from 1770 – circa 1785. He was a Captain in the militia and a leading member of the Committee of Safety.

In the early part of the Revolutionary War Jesse Brown was in the service of Connecticut as an express agent and confidential messenger. He participated in the Revolution by serving as the Governor’s Post. In September 1777, he brought news of the British Occupation of Philadelphia. The next month, he carried the news of the Second Continental Congress (in session at York Town, Pennsylvania) to Norwich.

After the war, in 1790, Brown operated a tavern in Norwich (shown on the left). It was said that his establishment was famous for its good dinners. In August 1797 President John Adams and his wife Abigail were guests at Jesse Brown’s Tavern.

He became a stage contractor and established lines between Boston and New York via Providence and Norwich. The communication with Boston was three times a week, the stage arriving on Sunday, Wednesday and Friday. The stage coach also ran to Hartford and New Haven.

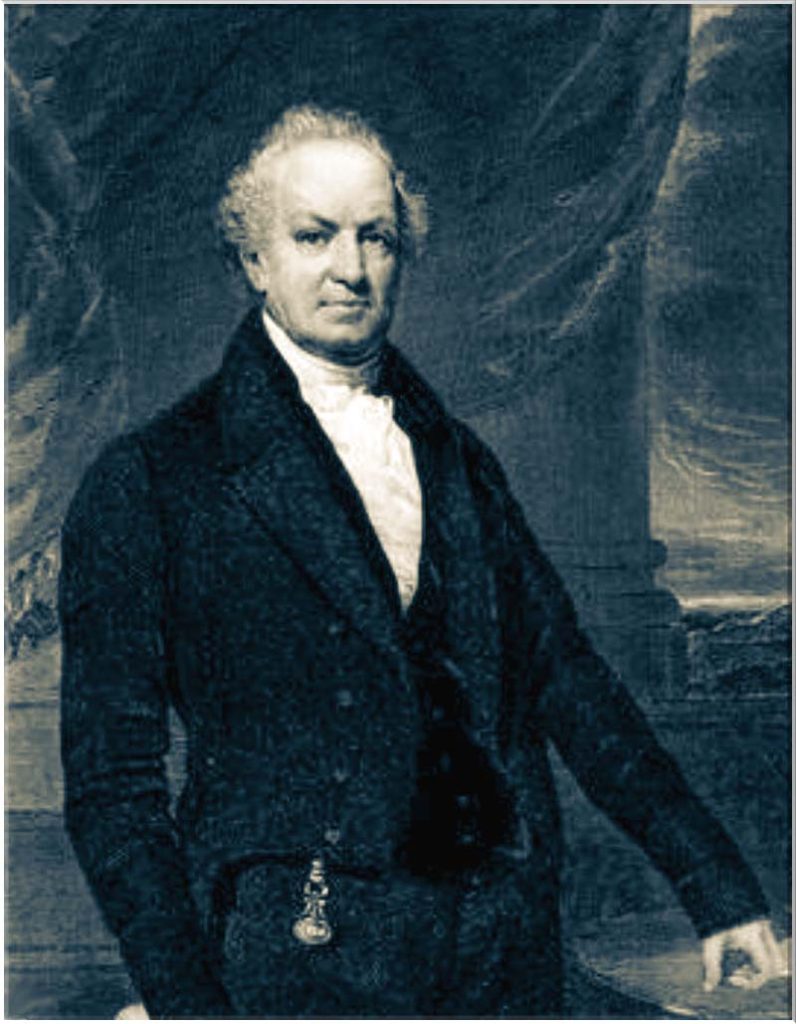

Shortly after the end of the Revolutionary War ended, Norwich was Incorporated and Benjamin Huntington was elected as Norwich’s first mayor. Benjamin was related to Samuel Huntington, signer of the Declaration of Independence. Benjamin’s grandfather Deacon Simon Huntington Jr., was also Samuel’s great grandfather.

Benjamin and Samuel served in the 2nd Continental Congress together from 1780 – March 1781. They also served together from March 1781 – July 1781 in the Confederation Congress. Benjamin and Samuel were related. Benjamin’s grandfather Simon Huntington Jr., was also Samuel’s great grandfather.

During the early months of the American Revolution, Benjamin Huntington was a member of Connecticut’s Committee of Safety. One of his relative’s, Jabez Huntington, was also on the Committee of Safety. Benjamin’s great-grandfather, Simon Huntington Sr., was also Jabez’s grandfather.

While on this committee, he played an integral part of procuring and refitting a navy vessel that was to be used as an intelligence gathering asset. The vessel was procured and then sailed into Norwich Harbor for refitting in August 1775. After the refitting was complete the vessel was christened the “Spy”. It became the first vessel of the Connecticut State Navy and was sent into action on October 7, 1775. The Spy, commanded by Captain Robert Niles, had a long successful tenure. Details for many more Norwich-based vessels that supported the war can be found HERE.

In 1976, The Spy was featured on the British Virgin Islands stamp, shown on the left, commemorating the United States Bicentennial.

Dr. Philip Turner was a well respected physician and surgeon practicing in Norwich in the late 1700s. Like many other other courageous men of Norwich at the time, he swiftly answered the call to service.

In June 1775, he came to the aid his fellow patriots at one of the first battles of the Revolutionary War, the Battle of Bunker Hill. At the time, Dr. Turner worked as a field military surgeon at the Connecticut Camp in Roxbury Massachusetts.

Later in the summer of 1777, he served the Continental Army as the assistant Surgeon of the Army Post at the Siege of Fort Ticonderoga in New York.

In 1777, Congress appointed Turner as Director General, later appointing him Surgeon General of the Eastern Department. He remained there until the end of the war.

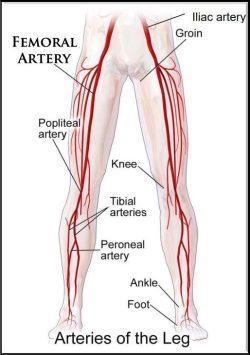

As still a relatively young man, Dr. Turner was the first surgeon in America to perform the operation of tying the femoral artery, which supplies blood to the leg. It is most likely that he developed and perfected the procedure while attending patriot soldiers who had suffered extensive damage to their legs from British weapons.

After Dr. Turner’s retirement from the Continental Army in 1781, Turner returned to Norwich. He resumed his private practice there as the leading surgeon in the eastern portion of the Connecticut, and some said in the entire state.

His home, at 29 West Town Street in Norwich, is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. He is buried in the Yantic Cemetery with military honors.

Benedict Arnold was born in Norwich on January 14, 1741. At a young age Benedict was sent to private school and it was expected that someday he would attend Yale College. However, his childhood family disintegrated upon the deaths of his mother, father, brother and two of his three sisters. He became both a hero and a treacherous traitor during the Revolutionary War.

Benedict Arnold began his militia career while in Norwich when he enlisted in the Connecticut Militia in August 1757 at the age of 16. His unit marched to the Lake George area of New York. However, before reaching their destination they received word that the French had already besieged Fort William Henry and their Indian allies had committed atrocities after their victory. Word of the siege’s disastrous outcome led the company to turn around. Arnold had served for only 13 days.

After the death of his mother, he and his only remaining sibling, Hannah, moved to New Haven where he became a successful druggist and merchant-sea captain.

While in New Haven, the Stamp Act of 1765 prompted Arnold to join the American patriot voices in opposition, and also led to his joining the Sons of Liberty. Arnold initially took no part in any public demonstrations, but, like many merchants in New Haven he continued to do business openly in defiance of the British Intolerable Acts.

In 1767 he married Margaret Mansfield, the daughter of New Haven’s sheriff. Over time they had 3 sons, Benedict VI, Richard and Henry.

A few years later, in March 1775, Benedict joined the colonist’s rebellion as a Captain in the New Haven militia. The next month his company marched northeast to assist in the Siege of Boston that followed the Battles of Lexington and Concord. He proposed an action to the Massachusetts Committee of Safety to seize Fort Ticonderoga in upstate New York, which he knew was poorly defended. Massachusetts issued him a Colonel’s commission on May 3, 1775, and he left Cambridge to join with Ethan Allen and his men in the May 10, 1775 Capture of Fort Ticonderoga in New York. As the first decisive victory of the Revolutionary War, this event provided both a morale booster and cannons that were later used by the colonists at the Siege of Boston.

A week later, on May 18, 1775 Colonel Arnold and his men travelled north and conducted a bold raid on Fort Saint-Jean, only a few miles south of Montreal. The fort was the Montreal’s principal defense. During this successful raid he captured the fort’s garrison and Lake Champlain’s only large military ship.

A few weeks later, after returning to Fort Ticonderoga, a Connecticut militia force arrived. Arnold had a dispute with its commander over who was to retain control of the fort. As a result, Arnold resigned his Massachusetts commission and left the fort.

On was on his way home from Ticonderoga in June 1775 Arnold learned that his wife, Margaret, had died. Their sons were only three, six and seven years old at the time.

Three months later he was commissioned as a Colonel in the Continental Army for an expedition to attack Quebec City in Canada. He and his 1,100 men left Cambridge for Quebec, however, it was a very difficult journey. Two hundred of his men died en route and another 300 turned back. After the siege he was promoted to Brigadier General.

After several successful campaigns in the Continental Army, Benedict Arnold became a trusted confidant of George Washington. Washington appointed Arnold the military commander of Philadelphia in 1778 after the British withdrew from the city.

Unfortunately, Arnold planned to capitalize financially on the change of power in Philadelphia and eventually betrayed the trust of George Washington and his fellow countrymen. Benedict Arnold will always be remembered as America’s most infamous traitor.

The life and times of Benedict Arnold are well documented. One well written book is “The Notorious Benedict Arnold : A True Story of Adventure, Heroism & Treachery“, by Steve Sheinkin.

After graduating with honors from Harvard College in 1763 Jedediah Huntington became associated with his father in commercial pursuits. He was engaged in this business when the Revolutionary cloud began to darken and soon became noted as one of the Sons of Liberty and an active Captain of the militia.

The revolutionary outbreak found him ready and able. Just one week after the firing of the first shot at the Battles of Lexington and Concord he reported to Cambridge Massachusetts with a regiment from Norwich under his command. He was ordered to occupy Dorchester Heights in March 1776. After the evacuation of Boston by the British, he and his army marched toward New York. Along the way, they stopped in Norwich at his father’s home in Norwich, where he entertained the Commander in Chief, George Washington.

Later, in December of 1777, General Huntington and his brigade, consisting of the 1st, 2nd, 5th, and 7th Connecticut Regiments, were among those with General Washington that arrived at the winter encampment at Valley Forge.

The Huntington Brigade stone marker at Valley Forge indicates where the soldiers of Connecticut built their huts and suffered through that long winter encampment. To ensure protection of the encampment from possible surprise attack, Washington ordered the construction of earthworks, and Huntington’s is among the few that survive today.

In May 1783, Huntington, along with Henry Knox, Edward Hand, and Samuel Shaw, wrote the Constitution of the Society of Cincinnati, essentially a social club for officers who had served in the Continental Army. The society still exists today, its membership limited to male descendants of officers of the Continental Army.

Jedediah Huntington met his second wife Anne in Peekskill New York, probably when his unit was based there in 1777. They married in 1778. They lived in Norwich at 23 East Town Street, which is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. General Huntington died in New London, September 25, 1818, where his remains were interred, though subsequently transferred to the family tomb in Old Norwichtown Cemetery.

Great Britain formally recognized the United States as an independent nation on September 3, 1783 by signing the Treaty of Paris. The Betsy Ross Flag shown on the left, with its 13 stars and stripes representing the former colonies, was flown proudly in Norwich. Norwich was incorporated as an official town in May 1784.

Prior to 1784 only five towns throughout all the colonies had been officially designated as cities. They were : 1) New York City, 2) Albany, 3) Philadelphia, 4) Richmond Virginia, and 5) Charleston South Carolina .

In the year 1784, the government of Connecticut incorporated five additional towns. The General Assembly, at its January session, granted such privileges to New Haven and New London. In its May session, Hartford, Middletown, and Norwich were also incorporated. These are now the oldest municipalities in New England.

None of the Connecticut prospective towns had over 4,000 inhabitants within their territory. All of them had conducted limited trade, using their ships, before the Revolutionary War. Thus, they were acquainted with commercial life.

A Proper Military Funeral For A Revolutionary War Veteran

*Place cursor over image to magnify

Memorial Day, originally known as Decoration Day, is the federal holiday for mourning U. S. military personnel who lost their lives while serving in the armed forces. Decoration Day began on May 30, 1868, and was designated as the day to honor Union soldiers who had died in battle. After World War I and II, the holiday turned into a remembrance for all soldiers who fought and died in the service. The holiday was known as Decoration Day until 1971, when Congress renamed it “Memorial Day.”

Joshua Yeomans is buried in Old Norwichtown cemetery.

Throughout our nation’s history veterans have been honored for their service in a variety of ways. The following article tells the story of how Joshua Yeomans, a Revolutionary War soldier, was honored in Norwich. He was born in 1752 and died on August 8, 1835. This article was printed in the Norwich Bulletin on Tuesday, November 16, 1897. It is believed that the author, C.A.C., was Charles A Converse, a Norwich industrialist.

MILITARY FUNERAL SIXTY YEARS AGO

Honors Paid a Revolutionary Soldier of Old Norwich

Burial Customs of the Past

Simplicity and Lack of Pomp the Rule

C. A. C. writes to the Bulletin:

Miss Caulkins relates in her history of Norwich that in August, 1835, Joshua Yeomans, a veteran of the revolution, died, and was buried with military honors. He lived for many years in the cottage on Lafayette Street, afterwards owned by Daniel Tree, and now occupied by Mr. Hunt, the florist.

Mr. Yeomans was one of the first men in this vicinity who responded to the call of liberty. He was present and fought at Bunker Hill, being one of the last men to leave the works, and he afterward served in the colonial armies until the end of the war. With the few remaining patriots of the revolution he was always invited to participate in the observance of Independence day in Norwich. In Boston the survivors of the battle of Bunker Hill were treated with distinguished consideration; and at the annual celebration of the Fourth of July they were honored guests. On one such occasion Mr. Yeomans was of the number invited to join his compatriots in Boston. On his return he related that he was not only invited to the public dinner at Faneuil hall, but he was taken in a carriage, with the mayor, and driven around Boston. He saw Bunker Hill, the Navy yard, the frigate Constitution, the old state house and the spot on State street below where the first revolutionary blood was shed by British red coats. He saw the cannon ball fired by Washington from Dorchester heights, and imbedded in the front wall of the Brattle street meeting house, and many other objects of interest. That visit to Boston was one of the happiest events of his life, and was always a green spot in his memory.

TOLLING THE BELL.

In those early days it was the general custom to toll the meeting house bell on the death of a person, afterwards striking the years of his age, followed by one additional stroke for a man and two for a woman. At funerals passing the bell would commence tolling when the body was placed in the hearse, and continue striking until the remains were deposited in the grave. The bell was also rung at the early morning for people to go to work, at noon for dinner, and the curfew at 9 o’clock admonished all to go to bed. On Sundays the bell was rung for people to assemble in the house of worship, and it tolled when the minister left his house, ceasing only when he arrived at the meeting house. In these days houses of worship were called meeting houses, the exception in town being Christ Episcopal church, which many persons declared was an offshoot of the church of Rome.

RIFLE GUARDS AS ESCORTS.

On the occasion of the death of this soldier and patriot it was deemed proper to give him a military funeral, and the Rifle guards, a company attached to the Eighteenth regiment, and of which the writer was a member, were invited to attend the obsequies and perform funeral escort to the grave. The invitation being accepted and the company ordered to parade, they met on the appointed day and marched to the residence of the deceased. On their arrival the funeral ceremonies had already commenced; the house was filled with mourning friends and relatives. Two ministers were present, one of whom gave an eloquent and impressive account of the life and service of the departed. A hymn was sung, followed by a concluding prayer, and the bearers, who were only selected at the time, as was the custom, came forward, after friends had viewed the remains, to take the coffin out to the hearse. the coffin was made of plain mahogany, with brass lifting handles at either end. There was no name plate. The initials of the deceased and his age were formed in the universal black letters and figures on top. No flowers of wreaths was placed on or around the coffin. Such tributes were not customary. It was only enshrouded in the flag under which the deceased had served his country so faithfully. The hearse was the property of the town. It had become rusty with age. There were no undertakers then, no private hearses, no professional nurses, The sick were cared for and attended by friends and neighbors. After death the corpse was never left alone; watchers were appointed for night and day, and funerals were conducted by some friend of the bereaved family.

THE FUNERAL PROCESSION.

The coffin had meantime been placed in the hearse, the military company had taken its place to lead the procession, ministers and bearers came next, then the hearse, with two pall bearers on each side, the mourners following, after them a few veterans, friends of the deceased, then friends and neighbors, all walking two by two. There were no public hacks in those days. At funerals everyone walked.

When all was ready, the order was given and the military led the mournful march, with flag folded, drums muffled and arms reversed. There were no military bands in those times outside the large cities. The music on this occasion was two snare drums and one bass drum and two fifes. At the first tap of the drum the passing bell commenced tolling and the cortege moved on. The stillness around seemed suited to the occasion. The day was lovely, the air tempered to a delicious mildness; summer had reached its meridian, and nature had put on her most glorious apparel; the fruit trees on each side were bending with golden fruit; the sumac and golden rod were glowing in crimson and gold; the willows seemed to bend to the occasion in silent respect, and all the gifts that a ripened summer holds were lavishly bestowed on every side. The sun was on its downward course in the west and in the blue ether above were only those glorious, great white fleecy clouds, ever changing in form and lazily rolling in the infinity of space.

SCENE AT THE GRAVE.

As the funeral procession moved on in silence and sadness, no sound was heard except the tap of the muffled drums and the mournful tone of the passing bell.

On reaching the old town graveyard the military formed in double platoons on each side of the open grave. The minister was followed by the bearers with the coffin, which was placed on supports over the grave. The mourners gathered inside of the military lines. The scene at this time was befitting the occasion; the coffin surrounded by the mourners, the military standing at rest, the great number of people outside with uncovered heads, standing among the graves of the fathers of the hamlet; the head stones with their quaint forms and inscriptions showing that many whose graves they marked had been buried more that 100 years. The sun was low down in the west, its rays illuminating the whole scene with almost supernatural brightness. The minister standing at the head of the grave having concluded his final prayer, as the coffin was lowered into the grave by the bearers repeated, “And now we commit the body of our departed friend to its last resting place, there to remain until the great Trump sounds on the resurrection morn.” At that moment the passing bell ceased tolling. Three volleys were fired by the military over the grave of the soldier and patriot, and all was over.

The military company then filed to the street, formed in platoons and followed by the procession, moved to the late residence of the deceased. Here they stood in two lines, with presented arms, while the mourners passed through their rank to the house. Afterward the friends dispersed to their homes. The military again formed in platoons and with flag unfurled, and quick music and quick step, marched to their armory and were dismissed.

I have thus described from memory the funeral of a revolutionary soldier, which took place more than sixty years ago and as for many years there had been no military obsequies on a funeral occasion, there was a large public attendance both at the house and at the grave.

Thanks to Richard Russ for researching this story