Sarah Harris Fayerweather (1812-1878)

Sarah Harris was born on April 16, 1812 in Norwich. She was the daughter of William Monteflora Harris and Sally Prentice Harris, both of whom were free farmers and resided in the Jail Hill section of Norwich.

At the age of 20 Sarah Harris requested admission to the Canterbury Female Boarding School operated by Prudence Crandall. In a letter to William Lloyd Garrison’s newspaper, The Liberator, Crandall recalls Sarah’s visit: “A colored girl of respectability – a professor of religion – and daughter of honorable parents, called on me sometime during the month of September last, and said in a very earnest manner, ‘Miss Crandall, I want to get a little more learning, enough if possible to teach colored children, and if you will admit me into your school I shall forever be under the greatest obligation to you. If you think it will be the means of injuring you, I will not insist on the favor.'”

After brief deliberation, Crandall admitted her to the school in September 1832 as the first black student. Shortly thereafter many parents of the other students demanded that Miss Crandall expel Sarah. When she refused, most of the other students withdrew. Faced with severe opposition from the Canterbury community, Crandall closed the existing school – only to reopen in 1833 in order to teach a group of solely African-American students.

Twenty nine years before the Civil War began, Sarah Harris Fayerweather, stood up for her rights and provided a fine example for how to begin to swing the pendulum of needed change. Simply put, she deeply desired to learn and to be able to teach others, and she was willing to stand up to the establishment to help make it happen. However, her journey, which began in Norwich, was anything but simple or easy.

Perhaps her bravery and actions displayed in 1832 sowed seeds of fairness in the hearts Norwich citizens who congregated at Breed Hall to discuss issues of slavery and pending war in 1861.

South Kingston Rhode Island

Sarah continued to attend the school in the face of harassment and adversity until Crandall, afraid for her pupils’ safety, after a mob converged on the school on the evening of Sarah’s marriage, closed the school permanently.

On September 9, 1834 Sarah married George Fayerweather Jr. in a double wedding ceremony with her brother and his bride in Canterbury. George was an accomplished blacksmith. The couple moved to New London in 1841 and then later to South Kingston Rhode Island in 1855. They lived in George’s blacksmith shop shown in the photo above. The house/shop was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1984.

Sarah Fayerweather joined the Kingston Anti-Slavery Society, attended antislavery meetings held by the American Anti-Slavery Society in various cities across the North, maintained a correspondence with her former teacher Prudence Crandall and former slave and abolitionist Frederick Douglass, and subscribed to The Liberator until Garrison ceased publishing it in 1865. She also maintained an active church life, joining the Sunday school class at Kingston’s Congregational church.

Sarah gave birth to five children. She named her first child Prudence Crandall. Sarah Harris Fayerweather is buried in South Kingston, Rhode Island in the Old Fernwood cemetery.

In 1970 Fayerweather Hall, a dormitory on the campus of University of Rhode Island, was named in honor of Sarah Harris Fayerweather. The Fayerweather Craft Guild, located in Kingston at the site of the Fayerweather family’s former home and blacksmith shop, is also named in her honor.

Acknowledgements

Wikipedia

Wikimedia Commons

The complete list of sources may be found by clicking the “Bibliography” button, and, then typing “Sarah Harris” in the SEARCH box.

Gertrude Haile Lanman (1850-1920)

Gertrude Haile was born on September 29, 1850, in Norwich, Connecticut, to Dr. Ashbel Bradford Haile and Mary Hall May of Savannah, Georgia. They were a family of distinction and wealth. Gertrude married William Camp Lanman, nephew of Commodore Joseph P. Lanman, on June 18, 1873, in Norwich. Her husband, William, was a partner in Lanman & Sevin druggists in Norwich. Due to poor health, he retired early in life, and the couple traveled internationally, spending quite a bit of time in Southern France and rural England. While in Europe, Gertrude took a special interest in art and was particularly fascinated by the cathedrals.

Her life story tells the tale of a generous, wealthy, attractive Norwich native and how she gave up all her wealth. Her final days were spent in poverty …

Gertrude Haile Lanman, sometimes known as Mary G., grew to become one of the most brilliant leaders of society in Norwich and one of the wealthiest women in the state of Connecticut; fortunes which she inherited with the passing of her father Dr. Ashbel B. Haile (1880) and an aunt, Miss Gertrude May of Savana, her name’s sake. She was also well known in the world of New York’s highest society and was accustomed to spending extended visits in exclusive hotels in Manhattan. The Lanman residence, located on Washington Street, was the focal point at which Gertrude hosted many lavish events. Called the “Ghlanbouer,” her residence was considered one of the showplaces of Norwich, where Gertrude entertained with exceptional elegance and grace.

Gertrude held a special concern for the health and well-being of all people, especially those in her native Norwich. Gertrude Lanman took the initiative to invite Miss Mable Boardman, National Chairperson of the Red Cross, to visit from Washington, D.C., to Norwich and tour her beautiful city. Miss Boardman spent several days getting to meet the people of Norwich and see the town while staying at “Ghlanbouer,” the Lanman family residence.

“Ghlanbouer,” ~ built 1895

The photo shows how Ghlanbouer appears today

*Place cursor over image to magnify

As a result, in 1909 the American National Red Cross chose to open a branch office in Norwich. At their first meeting Gertrude Lanman was elected secretary, an office she held for many years. Gertrude Lanman’s quality of love for others and desire for service was displayed when she led a woman’s group to Hartford in order to advocate for the construction of the state tuberculosis sanatorium before congress.

Following a successful vote, several state legislators reported that it was the influence of the women’s delegation from Norwich and Mrs. Gertrude Haile Lanman’s persuasive argument that influenced their vote to locate the sanatorium in Norwich. A sanatorium was opened in Norwich at Uncas on the Thames in February of 1913. All surgery performed in Connecticut was done under the direction of the Chief Surgeon, who had facilities at Uncas.

Using her wealth and political clout, Gertrude established the Haile Club (1907), a safe place for the welfare of young employed women, located in a three-story building on Main Street in Norwich. The Haile Club became home for many women. It was a place where they could find housing, food, receive medical care and counseling. There was a large auditorium where meetings were held. Gertrude Lanman managed the daily operations of the club and reported a membership of over 500 women under her care. In the late 1800s Suffragette meetings were routinely held at the Haile Club. During the summer months, Gertrude instituted a program where small groups of young women from New York City would come to Norwich to get away for a week and enjoy fresh healthy country air before returning to the city.

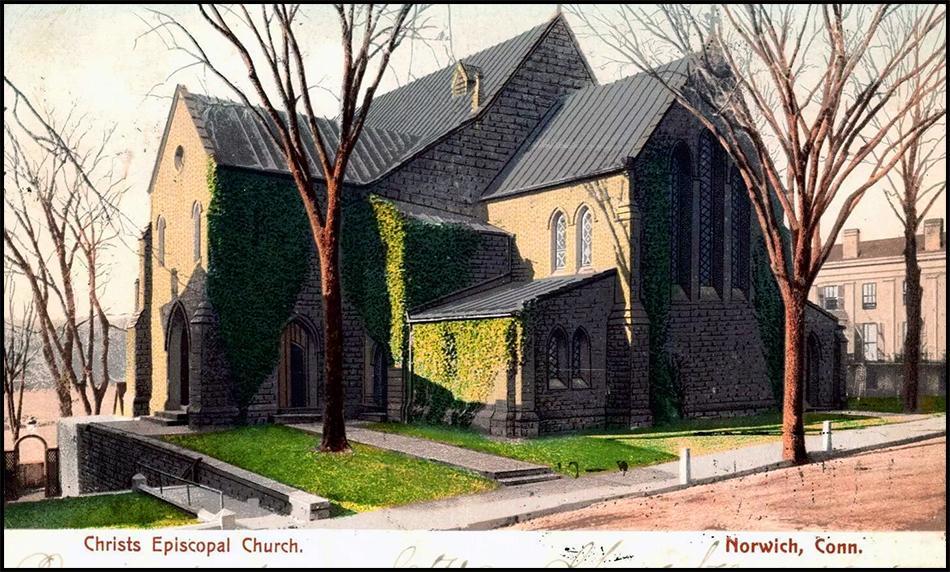

Following her husband’s death in 1903, Gertrude became a member of Christ Episcopal Church on Washington Street in Norwich. She is said to have given several thousand dollars to establish a Boys Club there.

Like many Victorian residences, the Lanman’s had a large greenhouse which held the highest quality plants and flowers. Gertrude was known for her love of flowers and organized the annual flower show held at the Norwich Amory. In 1910 her gardener, Charles Beasley, cultivated a new variety of chrysanthemum. It was a pure white variety which was officially registered under the name Gertrude H. Lanman chrysanthemum.

Gertrude’s character displayed a remarkable measure of humility which was matched by her unselfishness. She never complained or uttered bitter remarks when, years after her husband’s death, foolish investments made by close friends resulted in a good portion of her wealth to be lost.

As the years passed, Gertrude concentrated on living a more simplified spiritual life. In 1909 she became interested in and joined the Roman Catholic Church. In 1911 she traveled to New York City to be received into the Convent of the Sisters of the Reparation on East 29th Street.

She passed away on December 23, 1920. The article, shown below, was printed in the Norwich Bulletin o 12/28/1920. The article gives a detailed account of her life.

*Click on the 4-arrow symbol, on the upper-right corner of the article to expand the print

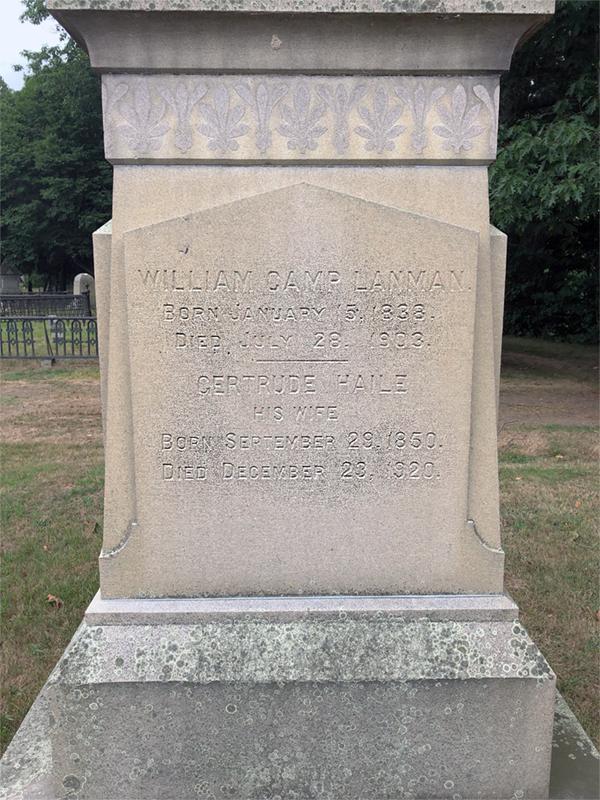

Grave Site in Yantic Cemetery

In keeping with the Scriptural instruction, it is easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than a rich man to enter the kingdom of heaven; Mrs. Lanman began the process of disposing of her jewels, art objects and her beautiful residence in Norwich, one of the most beautiful in all Connecticut. She donated $1,000,000 to the Catholic Church. Money from her collection of jewels went to the Haile Club.

New York Times

“Gertrude Haile Lanman has given up her riches to charity, renounced the world in general and social pleasures in particular, and begun the process of entering a convent by taking her vows as a Novitiate.

“I have tried all the pleasurers that the world has to offer. All are unsatisfying. My happiness henceforth will lie in following in our Lord’s footsteps and in laboring for others.” Mrs. Lanman said in parting from one of her dearest friends.

But, before Gertrude was able to complete her year of obligations and take her final vows, heart failure had physically weakened her and she was forced to withdraw from the process. Gertrude was able to stay with the sisters. Failing to qualify as a nun, Gertrude kept her vow of poverty and toiled as a common work woman to earn enough for the basic necessities of life.”

Gertrude died on 12/23/1920 at the age of 70 years-old. She and her husband are buried in Norwich’s Yantic Cemetery in Section 63 – Plot 15.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Dave Oat for researching and collecting almost all the information included in this article. And, thanks to Bruce Noland for colorizing the image of Gertrude Haile Lanman. There are a large number of additional articles surrounding the life and times of Gertrude Lanman provided in the bibliography.

Hutchinson Gazette, (08/27/ 1911) ~ colorized version of image by Bruce Noland

Christ Episcopal Church Postcard, 1906, Public Domain

Find A Grave

The complete list of sources may be found by clicking the “Bibliography” button, and, then typing “Gertrude” in the SEARCH box.

1861-1865 Soldiers' Aid Society

LIZZIE GREENE, CARRIE THOMAS & ELIZA PERKINS

The women of Norwich supported the Civil War effort in countless ways. Before, during and after the war they provided support and comfort to the men who had volunteered to serve.

When the call for volunteer soldiers first arrived in Norwich, the ladies immediately began to meet daily in Breed Hall to outfit their soldiers. By the time Captain Frank Chester and his men embarked on their duty, the women were credited with having made 1,600 flannel and checked cotton shirts and other articles of clothing.

The Soldiers’ Aid Society was organized in September 1861 in response to a request for socks from the soldiers. Elizabeth C. (Lizzie) Greene (William P. Greene’s younger daughter) led the organization and shared its management with Carrie L. Thomas and Eliza P. Perkins. During the latter part of the war Emeline Norton also held a responsible position in the Society’s management and gave of her time and strength to keep up its efforts.

From October 1861 through September 1865 the group raised more than $7,100 ($191,000 in today’s dollars). According to their records they expended $7,909 ($212,750 in today’s dollars) over the years. The bulk of their expenditures were from flannel, sheeting and yarn.

More than 60% of the deaths of Union soldiers came as a result of disease. The items provided by the Soldiers’ Aid Society were sorely needed by the soldiers. To help offset the soldiers’ physical needs the Society contributed much more than money. According to the group’s records, they sent thousands of personal items to the troops. Some of these were: 6,587 socks; 1,213 quilts; 2,018 pillow cases; 1,993 flannel shirts; 2,359 cotton shirts; 793 second hand shirts; and, not to be forgotten 1,519 drawers. These were but a few of many items sent.

A Civil War Union Hospital

*Place cursor over photo to magnify

Another important role for the Soldier’s Aid Society was to support regimental hospitals. At Governor Buckingham’s suggestion, an arrangement was made with the Society to supply regimental hospitals. The women of Norwich assumed special care for the soldiers of the 6th, 8th, 11th, and 13th CVI regiments. They invited women from Windham County and the rest of New London County to also join them in meeting the soldiers’ needs.

The Soldiers’ Aid Society also supported the war effort in other states. Dr. C.B. Webster sent a request from Washington to Norwich on February 7, 1863. His letter mentioned that his medical facility, the Contraband Camp Hospital, had 1,100 refugees from slavery, of which 300 were sick and under medical treatment. They were also treating 200 small pox patients.

Dr. Webb requested clothing, shoes and socks. The Soldiers’ Aid Society at once issued their call for contributions, and with the usual success. Many items were sent to the camp, which attested to the wide sympathy of the ladies and the promptness of their reply.

A Civil War Square Meal

*Place cursor over photo to magnify

In November 1862 Colonel J.H. Almy requested the Society to furnish pies of the Thanksgiving dinner of the Connecticut soldiers encamped on Long Island. The troops received 160 pies of various kinds; carefully packed in boxes.

Two years later when a second appeal for Thanksgiving, the Society once again generously supported their men with both food and money. The contributions filled 21 barrels and seven boxes, and were forwarded to the 8th, 9th, 10th, 11th, 13th, 21st and 29th regiments. $300 was spent on turkeys and chickens, $100 was spent on medical supplies, and $174 was spent on the comfort of the sick and wounded soldiers.

Lizzie Greene and Eliza Perkins also supported the fallen soldiers of Norwich after the war. In January 1869 it was resolved that a committee of seven would be appointed to solicit and collect funds for the erection of a monument to the Norwich soldiers and seamen who had fallen. This distinguished committee included William A. Buckingham, Elizabeth Greene and Eliza Perkins. The committee’s efforts, along with a city tax of assessment, and the sales of the “The Norwich Memorial” book (Info Source 1 below), funded the Civil War Soldiers’ Monument.

Much more detailed information about the Soldiers’ Aid Society can be found in Info Source 2.

Acknowledgements

“The Norwich Memorial: The Annals of Norwich, New London County, Connecticut in the Great Rebellion of 1861-65,” (1873), pp 177-201, by Malcom McGregor Dana

“Norwich and The Civil War,” pp 101-108, (2015), by Patricia F. Staley

National Archives

CivilWarAcademy.com

The complete list of sources may be found by clicking the “Bibliography” button, and, then typing “Soldiers’ Aid Society” in the SEARCH box.

Edith Carow Roosevelt (1861-1948)

Edith Kermit Carow was born in Norwich on August 6, 1861. She was born in her maternal parent’s mansion, 130 Washington Street. Her middle name was the surname of a paternal great-uncle Robert Kermit.

She married Theodore Roosevelt on December 2, 1886 who became the 26th President of the United States

in 1901. She served as First Lady from 1901-1909.

Edith led a very interesting life. In 1869-1871 she was schooled in the Dodsworth School for Dancing and Deportment, in New York City. In 1871-1879 she attended the Louise Comstock Private School, also in New York City. As a child, she attended private kindergarten and primary school at the Theodore Roosevelt Sr. home on Park Avenue in New York City.

She joined Theodore in many outdoor sporting activities, such as tennis, swimming long-distance, bicycling, and rowing. She also became an expert horsewoman.

She and her husband had four sons and one daughter.

Acknowledgements

National First Ladies Library

Historic Buildings of Connecticut

By Théobald Chartran

The complete list of sources may be found by clicking the “Bibliography” button, and, then typing “Edith” in the SEARCH box.

Dr. Ier J. Manwaring (1872-1958)

Dr. Ier J. Manwaring was one of Norwich’s first women medical doctors and one of the first female medical doctors to go overseas during an international conflict.

She was born in Montville but she and her parents moved to a 100-acre farm located on East Great Plain (present-day site of Three Rivers Community College) in Norwich when she was five years old. She was educated at the Broadway School, the East Greenwich Academy in Rhode Island, the Mary Baldwin College in Virginia, and the Women’s Medical College in Philadelphia. Upon completion of her education, she established her own medical practice in Norwich and was the physician at Connecticut College from 1916 until she left for France.

Dr. Manwaring, along with a contingent of other women doctors, was determined to serve her country after the United States entered World War I. The women doctors formed the American Women’s Hospitals Service (AWHS). It’s mission was to raise money to operate a hospital, staff it with doctors and nurses, and acquire and equip ambulances. Manwaring raised $5,000 in Connecticut.

AWHS established the first hospital in Neufmoutiers-en-Brie France in July 1918. When members of the first women’s hospital unit arrived, they could hear the thunder of artillery as the Allies in the Marne region stopped the Germans’ final offensive of the war. The women wore custom-designed khaki uniforms modeled after those of British officers.

Manwaring and 25 other doctors, nurses and drivers formed the second unit. Their destination, assigned by the French, was Luzancy on the Marne River. Residents of the area were returning to their homes from the war when the doctors opened their hospital in an old chateau — a place that the Germans had also used as a hospital.

During their service in France, the group treated more than 20,000 people in 195 villages, at an average cost of less than $1 per patient. From November 1918 to August 1919, the dispensary doctors made 8,348 house calls. They treated skin diseases, hernias, heart and kidney troubles in the old, and malnutrition in babies. They dressed abscesses and treated ulcers.

As the doctors prepared to leave Luzancy in March 1919, a ceremony was held in their honor. They were named honorary citizens of Luzancy and four of the doctors, including Manwaring, received medals, equivalent to the French Legion of Honor.

After her 14 month tour of duty she returned to Norwich to resume her medical practice.

She is buried in Maplewood Cemetery.

Acknowledgements

The complete list of sources may be found by clicking the “Bibliography” button, and, then typing “Dr. Ier” in the SEARCH box.