American Thermos Bottle Company

The American Thermos Bottle Company was added to the National Register of Historic Places on 07/17/1989. It located at 11 Thermos Avenue in Laurel Hill section of Norwich.

The following is an excerpt from Info Source 1:

“Once upon a time, life was more difficult before the invention of the thumbtack, the paper clip, Scotch Tape and the Thermos bottle. It is little things that make living endurable. Many of the little things we use every day are taken as a matter of fact.

The Thermos Bottle is one of those inventions, and Norwich had a major hand in its production.There was a time the Thermos Bottle Co. of Norwich was known worldwide. The contract between Norwich and Thermos demanded that whenever the word Thermos was used in an ad, it would include the name Norwich, Connecticut.

Thermos was, for so many years, a major industry in Norwich. Thermos settled here because of the ideal location on the Thames River and two railroads. They didn’t just pick the site; the City of Norwich went after them. Our local department of public utilities played a major hand, because they had the lowest electric rates in the state.”

“The site of the Thermos plant in Norwich had, for years, been the residence of Dr. William H. Mason. The town purchased the house and 27 acres for $750 an acre. The land was purchased an acre at a time by local citizens, and the City Hall bell would sound 10 times every time someone contributed $750.

Behind the campaign to bring Thermos to Norwich from Brooklyn, N.Y., was a group of 100 leading citizens know as the “Norwich Boomers.” They all had “Boomer badges” and sold them to everyone they met for $1 a piece. Attracting Thermos to Norwich was like a community celebration. There was a big city-wide ball that raised $2,000, and an auction at the ball raised another $544. In total, the people of the City of Norwich raised approximately $78,000.

In Feb. 14, 1912, an agreement was signed to make Norwich the home of the Thermos Bottle.”

The operation was shutdown in 1988.

Acknowledgements

“Thermos Was A Major Norwich Industry,” by Bill Stanley

United States Park Service

1stdlibs.com

Bean Hill Historic District

The Bean Hill Historic District is a well preserved group of twenty-three 18th and 19th century buildings focused on an ancient green near the Yantic River at Norwich’s western boundary.

In the 18th century Bean Hill was a manufacturing, commercial, and residential center. The enterprises there included a grist mill, a saw mill and at least one medium-sized textile mill. It was home to artisans, tavern keepers, and some workers in the local mill.

NOTABLE PLACES

- Bean Hill Plain: At the summit of Bean Hill is Bean Hill Plain (a.k.a. Bean Hill Green), an open square of land, once shaded by elm, ash, and poplar trees planted in 1729. It has been open, common land since the first settlement of Bean Hill and is the district’s focal point. The green is surrounded by eight buildings and the 1833 Bean Hill Methodist Church, the first in Norwich.

- Methodist Church 192 West Town Street: Major public structure, built in 1833 and altered in 1879. Early photographs of the church show it to be a humble but attractive structure of typically boxy meetinghouse proportions with long, round-headed windows, a two-tiered square steeple, and touches of classical ornament.

- Lt. Jacob Witter Tavern, 199 West Town Street: Meeting place for the Episcopal Church in the 1730s. It was also used as a tavern owned by Lt Jacob Witter in 1774. Military meetings were held here in 1784. The house was owned by Edmund Quincy Gookin in 1726.

- David Keeler House 200 West Town Street: circa 1870: The site is said to be the scene of the bean-pot discovery, giving way to the name Bean Hill. The spot is more certainly the site of an earlier house, known as the Lamb House. This house, believed to be the first house on Bean Hill, was demolished circa 1870 by David Keeler, a Bean Hill grocer.

- Bean Hill Tavern: The Bean Hill Tavern served as a meeting place for Norwich militia patriots. Major John Durkee, the tavern-keeper, spearheaded the drive against the Stamp Act. In 1765, Durkee earned a spot in Connecticut history when he led a band of liberty men who intercepted Stamp Distributor, Jared Ingersoll, at Wethersfield and forced Ingersoll’s resignation; for this act, Durkee was known thereafter as the “Bold Bean Hiller.”

- Aaron Cleveland Hat Shop and William Cleveland’s Jewelry & Clock Shop: Bean Hill’s citizens were humble people, respected but not renowned. There are, however, several prominent exceptions. The Clevelands were a noteworthy family who lived on Bean Hill. Aaron Cleveland , who ran a Bean Hill hat shop (now standing at 122 West Town Street, but originally located next to the Methodist Church) was an early abolitionist who wrote poems, essays, and sermons on the political, social, and religious questions of the day. He was President Grover Cleveland’s great-grandfather. His son, Deacon William Cleveland, was a silversmith and clock maker on Bean Hill and was President Grover Cleveland’s grandfather.

- Jarvis Hyde House: 5 Huntington Ave: 1780: May have been Hyde’s Tavern

- David Ruggles’ Harents’ House: Sylvia Lane

Info Source 1 provides a more complete list of Bean Hill historic places.

HOW BEAN HILL GOT ITS NAME

There are several popular legends as to how Bean Hill got its name. The following is an excerpt from Info Source 2: “The origin of the savory old name, Bean Hill, is thoroughly affirmed, I think, by several histories of the settlement of New England, which assert that those who first visited this region were prospectors under an invitation from Uncas. They struck upon this cozy little patch of table land having its rear a rolling meadow in its warm southern front divided by a beautiful fish-stocked river, beyond which lay another strip of tableland skirted by a romantic range of highlands, the Wawecus Hills. The weary and hungry prospectors, being favorably impressed with the locality, halted, and casting about for greatly needed food, they discovered pots of beans deposited in the earth. Considering them an equivalent to the manna sent to the Israelites, they joyfully appropriated them, and for the time being acknowledged with thanksgiving the providential meal, since which time, and most appropriately, too, not only upon and around this original Puritan bean mount, but wherever the foot of her descendants press the soil, the savory rye and Indian bread and dish of baked beans continues to be the Saturday night and seventh-day meal.”NOTABLE PEOPLE

Bean Hillers were strong advocates for both religious and political freedom in 1700’s and 1800’s. Dissenters from the Congregational Church met at Bean Hill in 1745 and the first Episcopal services in Norwich were held here in 1738. Early Methodists also worshipped here. Many political speeches and public gatherings were held under a large elm tree on the green.

Notables Bean Hillers include:

- Major John Durkee : A leader of the Sons of Liberty, who opposed the British Stamp Act in 1765. Hosted gatherings in his tavern on Bean Hill

- Aaron Cleveland Jr. : Great-grandfather of Grover Cleveland. He operated a hat shop on Bean Hill, openly opposed slavery in 1774 and became a Congregational pastor in Hartford.

- Deacon William Cleveland : Grandfather of Grover Cleveland : Ran a jewelry shop, was a Deacon at the 1st Congregational Church.

- David Ruggles : African American born here in 1810 : A major figure in the Underground Railroad

- David C. Case : A Norwich native: Norwich’s first casualty in the Civil War

- John Baldwin : One of Norwich’s founding fathers, lived at 210 West Town Street. He was the ancestor of three Connecticut governors, Roger Sherman Baldwin (in office 1844-1846), Simeon Baldwin (in office 1911-1915) and Raymond E. Baldwin (in office 1939-1941) & (1943-1946). John Baldwin is buried in the Founders’ Cemetery. John raised the basic frame of the their house in 1660 as a saltbox and his family came in 1661. Around 1743 the brothers, Elisha and Hezekiah Edgerton, bought the house and raised the roof to a full two stories with a large attic. They moved in their combined family of thirteen children and were resident until around 1783.

- Simeon Baldwin : Was born in Norwich and lived his early life on Bean Hill at 213 West Town Street. Judge Simeon Baldwin, (1761-1851), became the first Secretary of the Connecticut Anti-Slavery Society at its founding in 1790. In 1826, he was the mayor of New Haven. He married twice, first Elizabeth Sherman, and then, after Elizabeth’s death, her sister Rebecca. They were both daughters of Roger Sherman, signer of the Declaration of Independence. He was the father of Connecticut Governor Roger Sherman Baldwin and the grandfather of Connecticut Governor Simeon Eben Baldwin. The Simeon Baldwin house was moved to Natick, Massachusetts in 1934.

- Elisha Hyde : 3rd Mayor of Norwich

- John Pease : One of the 35 Norwich founding fathers. Perfected New England clam chowder recipe

BEAN HILL POTTERY

Excerpt from Info Source 3: “At Bean Hill was one of the first potteries in this country. They manufactured a yellow brown salt-glazed earthenware, of which there are a very few specimens in existence. This salt-glaze was discovered about 1680 by a servant who lived on the farm of a Mr. Yale. There was an earthen vessel on the fire with brine in it to cure pork. While the servant was away the brine boiled over, the pot became red hot, and the sides were found to be glazed. A potter utilized the discovery and the salt-glaze became an established fact.”

The Bean Hill Historic District was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1982.

Acknowledgements

United States Park Service

“Reminiscences of Bean Hill,” (1896), p 295, by Burrell W. Hyde

“Norwich: Early Homes and History, A Paper Written and Delivered by Sarah Lester Tyler,” p 19, published by Faith Trumbull Chapter, D.A.R., Norwich, CT, 1906

“Reminiscences of Bean Hill,” (1896), p 448, by Burrell W. Hyde

The complete list of sources may be found by clicking the “Bibliography” button, and, then typing “Bean Hill” in the SEARCH box.

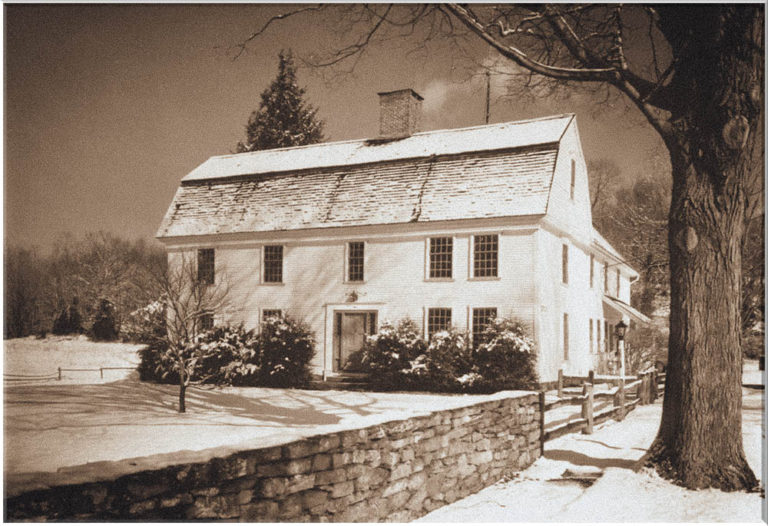

Bradford-Huntington House

The Bradford-Huntington house, located at 16 Huntington Lane, lies in the northern section of the Norwichtown Historic District. It was occupied by Simon Huntington and later by Major General Jabez Huntington. Simon Huntington’s father, Deacon Simon Huntington, was a founding father of Norwich, and, Jabez Huntington knew George Washington. His son, Jedediah Huntington, was a Revolutionary War general, and worked closely with George Washington on several occasions. In 1776 George Washington spent the night in the Bradford-Huntington house, and there is evidence that Marquis de Lafayette also visited General Huntington during the Revolutionary War period.

Major General Jabez Huntington owned a large number of vessels engaged in the West Indian trade. He represented Norwich in the General Assembly, served on the Committee of Safety and in 1776 was appointed one of the two Major Generals of the Connecticut militia.

The first portion of the house was built by John Bradford’s son, Thomas, circa 1660. Later portions of the house were added by Simon Huntington Jr. between 1691 and 1719. A third stage of additions was added in the 1740 time frame.

The Bradford-Huntington house was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1970.

Acknowledgements

United States Park Service

“Old Houses of the Ancient Town of Norwich, 1600-1800,” (1895), pp 282-283, by Mary Elizabeth Perkins

Constance Luyster, 1970

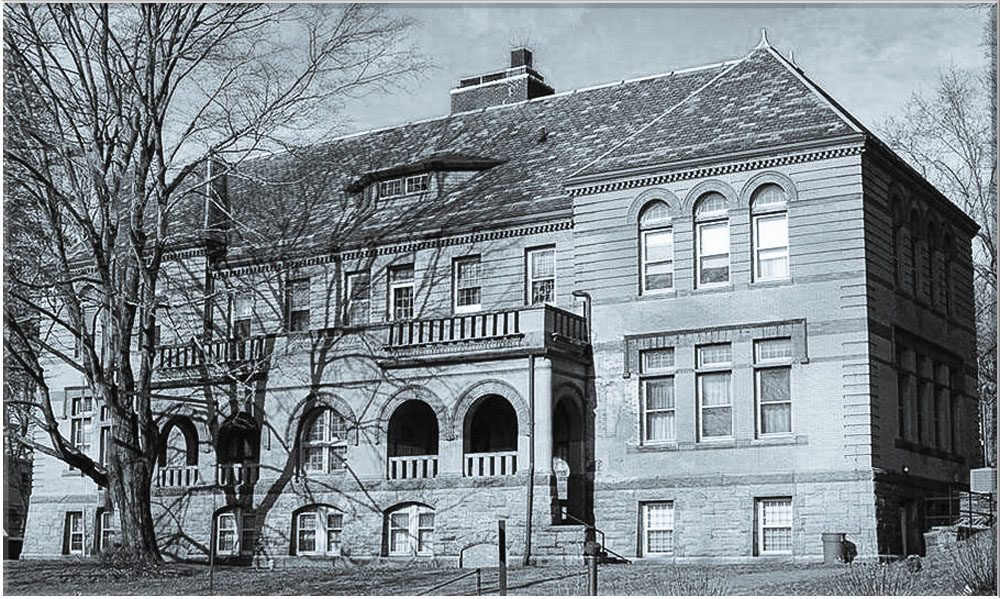

Broad Street School

The Broad Street School, located in the Chelsea Parade Historic District at 100 Broad Street, was built in 1897. It is a yellow-brick, two-story structure built in the Romanesque Revival style. It is significant because it reflects the historical development of Norwich, a thriving mercantile and industrial center in the 19th century, and because it exemplifies turn-of-the-century educational philosophy. The school was the largest and most ornate school built by the Norwich Central School District in a major rebuilding program in the 1890s. It attracted enough attention to be included as one of the up-to-date school buildings featured in a special section of the State Board of Education’s Annual Report of 1902.

The Broad Street School is architecturally significant as a richly decorated example of the Romanesque Revival style, designed by a noted school architect, Wilson Potter, of New York City. Meticulous attention to detail and the use of quality materials is exhibited throughout.

The Norwich Central School District commissioned the architect Wilson Potter to design its new elementary school. Potter made a specialty of school architecture and his works include New York City’s Fulton High School, Bristol (Connecticut) High School, and another Norwich school in Laurel Hill.

The mere fact that a renowned architect was hired to design Broad Street School indicates the character of the neighborhood in which it was located. Broad Street and Washington Avenue area was inhabited by Norwich’s social and economic elite.

Norwich was an important port city, strategically located on the Thames River, and an industrial center in eastern Connecticut throughout the 19th century. The affluent citizens of the Broad Street School district wanted a handsome school which would reflect the progressive and proper image of the community which it served, and thus the school board hired a notable architect. As a point of comparison, the Laurel Hill School, also designed by Wilson Potter, is nearly identical in form but lacks most of the ornamentation found in Broad Street School.

The Broad Street School closed in the late 1970s, and has been converted to residential use. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1984.

Acknowledgements

United States Park Service

Realtor.com

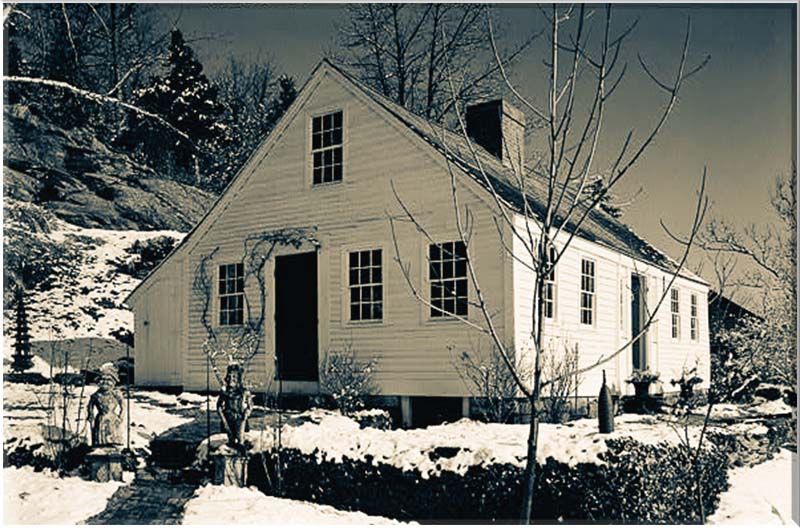

Captain Richard Charlton House

The Captain Richard Charlton House at 12 Mediterranean Lane is one of many houses listed on the National Register of Historic Places located in the Norwichtown Historic District. The original house was probably built as a seaman’s hideaway for Captain Richard Charlton.

The land was deeded to Richard Charlton in 1741, and the house was first built by his youngest son, Samuel Charlton. Samuel fought in the Revolutionary War and died in a British prison ship (most likely the HMS Jersey) in New York Harbor.

The house, in its present form, was built around 1800. It is an 18’ x 29’ building, five bays wide and one and a half stories high. It has a stone foundation, and the frame is made of chestnut and oak. It is believed that it was built with framing timbers from Charlton’s original house.

The house is heated with two fireplaces and an oil stove. The brick fireplaces are very shallow and have plastered faces painted red in the manner typical of Norwich fireplaces. Left of one of the fireplaces is an oval-shaped oven with a domed roof.

The building underwent a significant restoration in the 20th century by Raymond B. Case. Memorabilia of the sailor’s life in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries fill the walls. These include a written guarantee of the privileges of a Nantucket man, harpoons, and a painted wooden ship figurehead (shown on the left).

According to family records, Richard Charlton was born in England circa 1715 and moved to Norwich before 1741. He married Sarah Grist (1722-1808) in 1742. They had seven children. The first child, also named Sarah, was born in the 1742-1743 time frame. Their last child was Samuel, born in 1756.

In 1755, Richard sold the western part of his house-lot and one of his shops to Simeon Carew. The following year, he created a will that was prefaced by: “being bound to a voyage to sea.” Most likely, he had been conscripted to fight for Britain in the French and Indian War, which lasted from 1754 to 1763. He died the following year, 1757. It was written in his family’s Bible that, “he was blown up in a vessel at the rejoicings at the capture of Havana in 1757”.

The house was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1970.

Acknowledgements

United States Park Service

“Old Houses of the Ancient Town of Norwich, 1600-1800,” (1895), (pgs 168, 251,252 440), by Mary Elizabeth Perkins

Jack E. Boucher

Library of Congress