1853 Train Accident on the New London,

Willimantic & Palmer Line

The New London, Willimantic & Palmer Railroad (NLW&P) was was the first railroad to provide a direct rail line between Norwich and New London. Prior to 1848 travelers had to take a steamship from Chelsea Harbor to the mouth of the Thames.

In general, passengers and freight was transported quickly and safely. However, on March 17, 1853 the train ran off the rails. Wood-engraving from the Illustrated News, April 16, 1853. The accident occurred about two miles south of the city of Norwich on March 17, 1853. A locomotive on the New London, Willimantic & Palmer Railroad ran off the track and ran into a house, detaching the kitchen and buttery. A woman inside the house was injured but no one was killed. An article Illustrated News 04/16/1853 magazine states:

*Place cursor over image to magnify

“I send you enclosed a rough sketch of a very singular railroad accident, which occurred on the 17th of the prior month, on the N.L. P. & Willimantic Railroad, about two miles below the city of Norwich Connecticut. The road winds along by the side of the beautiful river Thames, and the spot where the accident took place is one of the most romantic that could be imagined.”

“As you can see by the drawing, a short curve is taken between the house and the ridge on the left. The train was under full headway – running too fast, detaching itself from the cars, and cut through and into the house on the right, tearing away.”

Acknowledgements

Wikipedia

Railway & Locomotive Historical Society

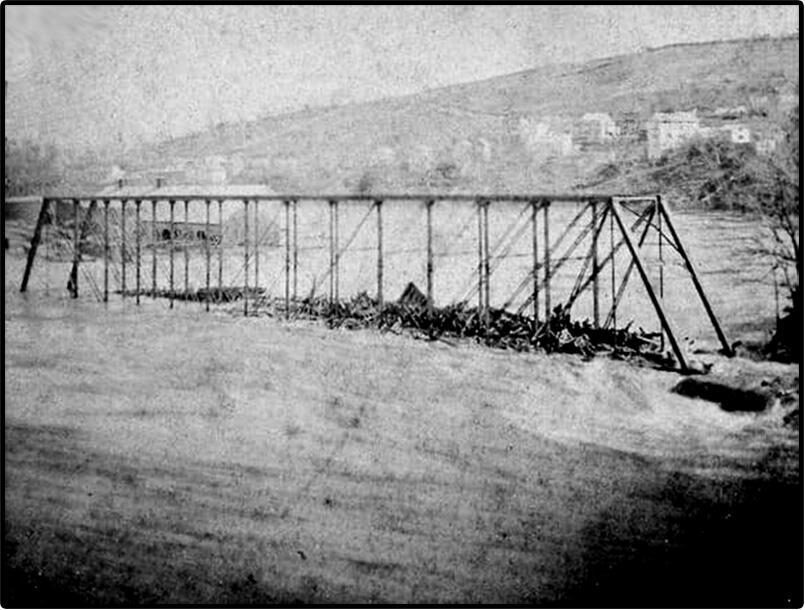

1869 Railroad Swing Bridge Accident

Click on the two right-facing symbols >> at the top-right corner & click “Presentation Mode” to read article

On Saturday July 17, 1869 one of the Norwich & Worcester Railroad engineers needed to transport seventy rail cars filled with coal. Unfortunately, the train crashed during the task. The Bulletin newspaper article, shown on the left, printed two days after the incident, provides details.

In 1869 coal was often shipped up the Thames River from New London to Allyn’s Point and then transported by rail to Norwich.

According to Info Source 2: “The number of steamers of the “Norwich Line” that discharged freights at Allyn’s Point and at wharf in Norwich to be transported north by the Norwich & Worcester Railroad, was 185 ; and the number of sail vessels with coal, pig iron, steel billets, etc., landing at the same places for railroad transportation was 450.”

This freight train was probably intended to transport coal from Allyn’s Point to one of the coal yards in Norwich.

*Place cursor over image to magnify

A map of the most likely journey of the Norwich & Worcester locomotive “Thames,” is shown on the left. The train’s engineer (John Calebs), his two young children, the locomotive’s fireman (John Roath), and the train’s brakeman likely boarded the train at the railroad company’s “Roundhouse.” The company’s rail cars and engines were often stored in the roundhouse.

From the roundhouse Mr. Calebs backed the locomotive past the Laurel Hill pedestrian bridge and then over the railroad bridge.

Upon review of the photograph, below-left, one can see that the position of the swing gate determined whether the train would travel to the terminal OR the railroad bridge. The OPEN position allowed passage to the terminal and the CLOSED position allowed passage to the bridge.

After the engine cleared the railroad bridge entrance, the swing gate was put into the OPEN position by David Barry, the man in charge of opening and closing the swing gate. Mr. Barry believed that Calebs and the train pulling the coal-filled rail cars would not be back for “some time,” so he opened the gate to the terminal.

*Place cursor over images to magnify

After Calebs reached his destination and attached the seventy coal cars he started back toward Norwich. When the train was about halfway across the bridge, Calebs, seeing the gate open, reversed the engine, sounded the alarm whistle, and took his two small children, whom he had been giving a ride, into his arms and jumped upon the bridge. The fireman, Charles Roath, jumped off on the other side.

There was only one brakeman on the train, and notwithstanding, the reversing of the engine, she was pressed forward by the seventy coal cars behind, passing over the edge of the wall and dropping down upon the lower track, fifteen feet below. The resting place of the locomotive is shown in the upper-right photograph.

The accident took place around noon and by 9 pm the tracks were cleared. The time needed to restore order severely delayed several other trains.

The newspaper article ends with, “Some of the railroad officials think the engineer was, in a measure, to blame for leaving his children on the engine, as had they not been there and taken up with his attention, he would most probably have seen that the gate was open as soon as he got upon the bridge. The damage to the engine will not be very great, and will soon be repaired at the company’s machine shop to which it has been taken.”

Acknowledgements

“The Faith Jennings Collection,” 1997, p 136

“On the Track,” 07/19/1869, p 2

“Norwich Connecticut: Its Importance as a Business and Manufacturing Centre and as a Place of Residence” (1888), page 44, by the Norwich Board of Trade

The complete list of sources may be found by clicking the “Bibliography” button, and, then typing “1869 swing bridge” in the SEARCH box.

1876 Almshouse Fire

Norwich has made provision for poor and/or mentally disabled people for hundreds of years. Throughout New England, prior to 1800, poorhouses frequently settled near adjacent farms where paupers could labor to raise their own food, care for animals, and contribute to their welfare and upkeep as much as possible. These farms were commonly called “poor farms” the extent and locations of which varied widely from town to town.

From 1790-1800 Norwich citizens in need of these services were sent to the Hazen Farm in Baltic. The town of Norwich provided funds for residents at the farm, however, due to its location far away from the hub of Norwich, the costs were high.

In 1800 a more cost-effective poor house, located on Washington Street near the heart of Norwich proper, was established. The facility, the first Almshouse in Norwich, put into service in 1800. However, as the city prospered, successful merchants, bankers, manufactures and sea captains who owned mansions on Washington Street forced the poor farm to move to a more “suitable” location.

In 1819 a new Almshouse was built on the west side of the Yantic River, near the present-day Estelle Cohen Dog Park on Asylum Street. Over the years, both poor and mentally disabled were cared for in the facility.

Click on the two right-facing symbols >> at the top-right corner & click “Presentation Mode” to read article

On March 12, 1876 a diastrous fire engulfed the Almshouse. While almost all 51 Almshouse patients were sleeping, a fire caused by a coal-burning furnace in building’s cellar sparked to life. A graphic, detailed account of the tragedy is provided in the newspaper article shown on the left. It is believed that 15 souls were lost, 14 were accounted for, and many of the remaining souls were severely injured.

Almshouse 1876 After fire

Photographed by Faith Jennings

The Almshouse was rebuilt and the new facility, as appeared in 1898 is shown above. Upon the opening of the Norwich State Hospital for the Insane in October 1904 the mentally disturbed residents from the Almshouse were moved to the Hospital.

*Place cursor over images to magnify

Acknowledgements

Almshouse Conflagration, by Indiana Sentinel, Vol. 25, No. 32, p 2 , (03/22/1876)

‘New’ Almshouse, 1898 on Asylum Street ~ colorized and posted by Bruce Noland

The complete list of sources may be found by clicking the “Bibliography” button, and, then typing “Almshouse” in the SEARCH box.

Flood of 1876

Two weeks after the Almshouse fire, on March 26, 1876, Norwich suffered a flood that caused widespread damage and loss of life.

Heavy rains, over an extended period, filled the reservoirs along the Yantic, Quinebaug, and Shetucket Rivers. The first notice that Norwich citizens heard was the alarm of the city hall bell. The bell was a summons for assistance to clear the warehouses on the riverfront, as the immense volumes of water discharged from the three rivers. The water level of the Thames rose above the wharves and serious destruction of property resulted throughout much of downtown Norwich.

Thankfully, the Greeneville Dam held despite twelve feet of water flowing over it. The Taftville Dam also held with ten feet of water flowing over its spillway. The most severe damage was inflicted on the Baltic Dam. Its bulkhead washed away, and the dam was undermined.

Seven people died, and the loss was estimated at $500,000 ($12,000,000 in today’s dollars). The Norwich & Worcester sections of the New York and New England Railroad, and the New London Northern Railroad was badly washed out in several places.

Acknowledgements

Hartford Daily Courant 03/27/1876

Connecticut Historical Society

The complete list of sources may be found by clicking the “Bibliography” button, and, then typing “1876 flood” in the SEARCH box.

1888 Taftville Sacred Heart School & Convent Fire

In 1888, the Sacred Heart School on School Street in Taftville was completely destroyed and the convent next door was badly damaged in a fire. Since there was no fire protection for the village, a small bucket brigade fought the fire until a Steamer Engine from Norwich could arrive but it was too late for the school.

The school, built in 1886, is shown below-left. The school and convent, after the 1888 fire, is shown below-right.

*Place cursor over image to magnify

NOTE: A much more comprehensive history of the Taftville Fire Department is available at the link below.

Acknowledgements

“Village of Taftville Fire History,” by the Taftville No. 2 Fire Department

“Sacred Heart School in Taftville Celebrates 100 Years,” 06/03/2009, by Michael Gannon